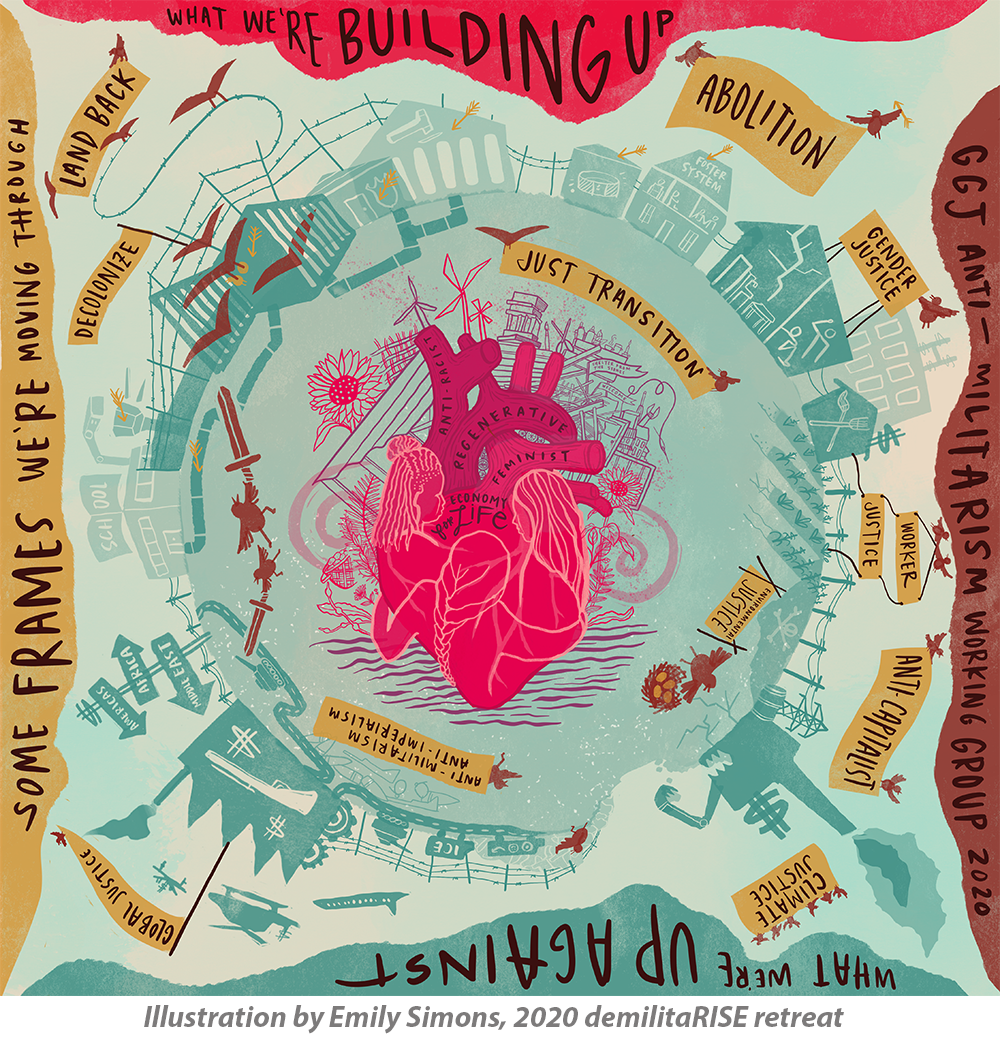

“If all we do is fight against what we don’t want, we learn to love the fight and have nothing left for our vision but longing. But longing isn’t good enough. We must live into the vision by creating it and defending it. We must ‘Build the New’ as a way to ‘Stop the Bad’ —we must be both visionary and oppositional. This doesn’t mean we don’t resist, but we have to organize ourselves into applying our labor to meet our needs rooted in our cultures and visions”

Overview

Our current racial capitalist system is powered by an extractive energy model - one that sacrifices the health and wellbeing of people and ecosystems for the sake of profit and growth. Cheap nonrenewable energy and minerals, that took millions of years to form, have been fueling the economy of growth for the past 150 years and their extraction is becoming exponentially more destructive. The global demand for energy continues to grow at around 2% annually and all forms of energy use are growing together: gas, coal, oil, nuclear and renewables.

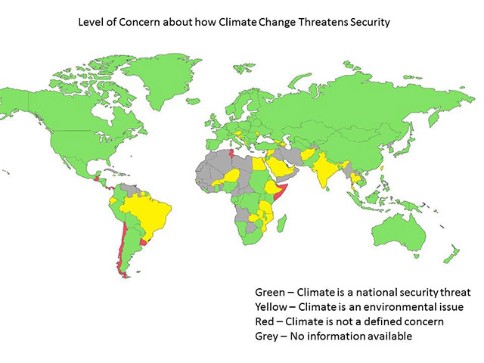

While the awareness around planetary destruction caused by fossil fuels has grown, many solutions do not adequately address the systemic causes for the energy crisis, and are simply looking for alternative - seemingly “greener” - ways to fuel capitalism. Reversing this growth and expansion of the energy sector is an urgent and essential step in building an alternative energy system. Climate and environmental justice groups have been calling for a shift from a corporate centralized energy system to one that is localized - produced, owned and governed by communities. Energy justice calls to end market-based mechanisms that impair efforts to truly end fossil fuel pollution disproportionately affecting low income and communities of color, and to stop false solutions that seek corporate industrialized “green” alternatives instead of systemic change of the energy system.

Working towards an alternative energy system comes in tandem with transforming the economy. We must step away from the fuel-dependent extractivist and growth-based system we currently live in towards a localized, community-driven, and regenerative one (read more about that on our Economy page). Without a comprehensive plan to transform how and why we use fuel and stepping away from extractivist economy, no alternative methods of energy production and distribution would provide the kind of transformation communities and the planet require. Thus, the alternatives proposed in this section are rooted in a collective and systemic overhaul of how dependent capitalist lifestyles are on a constant consumption of energy (whether it is “renewable” or fossil fuel-based).

Way Forward

Way forward 1:

Energy Democracy

As defined by Climate Justice Alliance, “Energy Democracy frames the international struggle of working people, low-income communities, Asian and Pacific Islander, Black, Brown, and Indigenous nations and their communities to take control of energy resources from the energy establishment and use those resources to empower their communities literally (by providing energy), economically, and politically. It means bringing energy resources under public or community ownership and/or governance.”

Organizations leading the way in Energy Democracy:

Climate Justice Alliance’s Energy Democracy working group (EnDEM)

The Our Power Plan: Charting a Path to Climate Justice - The plan urges federal and state decision-makers to assure that frontline environmental justice communities and workers be primary stakeholders in the implementation process of the Clean Power Plan "Uprose" by 350.org is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 - 2017

"Uprose" by 350.org is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 - 2017

UPROSE

Uprose works in the interest of a Just Transition, a move away from the extraction economy and towards climate solutions that put frontline communities in positions of leadership.- Sunset Park Solar is New York City’s first community solar project owned and operated by a cooperative for the benefit of local residents and businesses. It is a 685 kilowatt solar project that will be built on the Brooklyn Army Terminal rooftop.

Institute for Local Self-Reliance

ILSR provides technical assistance to communities about local solutions for sustainable community development in areas such as banking, broadband, energy, and waste through local purchasing.- Community Power Interactive Toolkit

- Beyond Sharing: How Communities Can Take Ownership of Renewable Power

- Local Energy Rules [Podcast Series]

- Community Power Map

ESKOM Research Reference Group: Achieving a Just Transition for South Africa.

- Alternative Information and Development Centre (AIDC), Trade Unions for Energy Democracy (TUED), and South Africa's National Union of Metalworkers (NUMSA), Transnational Institute (TNI) and National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) are developing a road map to establish a new public electricity system based on a progressive energy transition and restructuring of Eskom, the South Africa’s state-owned power company.

- What Is Energy Democracy? Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung

Instituto de Ecología Política (IEP) / Institute of Political Ecology (IPE) - Chile

IEP’s work has been carried out through education for sustainability, research, strengthening civil society, education and reporting campaigns, and legal actions in the defense of the environment and people; through the creation of strategic alliances and the development of public policies the right to live in a healthy environment can be guaranteed.- Camino Solar: An initiative by IEP to promote citizen participation in the generation of photovoltaic energy, in order to contribute to the decentralization and democratization of the transition towards an energy model based on renewable energies. [Video]

Centre for Environment and Energy Development - India

CEED is a solution-driven organization that works towards creating inspiring solutions to maintain a healthy, clean and sustainable environment- 100% Renewable Energy (RE) Bihar - A Guide Map

- CEED decentralized renewable energy [Video]

More Resources on Energy Democracy

Books, Articles, and Reports

- Energy Democracy: Advancing Equity in Clean Energy Solutions, edited by Denise Fairchild, Al Weinrub

- “Energy Democracy: Community-Led Solutions – Three Case Studies” by Center for Social Inclusion

- Tracing the emerging energy transitions in the Global North and the Global South - Authors: Ortzi Akizu, Leire Urkidi, Gorka Bueno, Rosa Lago, Iñaki Barcena, Martin Mantxo, Izaro Basurko, Jose Manuel Lopez-Guede

- Democratizing Energy to Counter the Climate Catastrophe, Resilience.org

- Potencial Cooperativas ERNC en América Latina - Instituto de Ecología Política (IEP) [Paper, ES]

- Principals of Energy Democracy

- Seminario propone potenciar cooperativas de energía en Latinoamérica - Instituto de Ecología Política (IEP) [Article, ES]

- Towards Energy Democracy, TNI

- The Future is Public: Democratic Ownership of Public Services, TNI

- A renewable energy model based on participation, collective ownership and gender equity, TNI

- Hundreds of Thousands Are Without Power Thanks to PG&E. This Shows Why We Need Public Ownership, In These Times

- Energy Democracy: Redistributing Power to the People Through Renewable Transformation

- The Energy Democracy Flipbook, curated by Emerald Cities Collaborative

- Utility Justice Campaign (California-based campaign for a safe, reliable, community-and-worker-owned energy system)

- The PG&E Bailout and What It Means for You, Utility Justice Campaign (California)

- Leap Manifesto: A Call for Canada Based on Caring for the Earth and One Another

- Towards Energy Democracy, TNI

- Wildfires, Shutoffs, And A Just Transition, Movement Generation

- Life After Mining, Yes to Life, No to Mining

Way forward 2:

Renewable Energy

While renewable energy has been rapidly growing in popularity as the only viable alternative source of energy for a sustainable future, conversations around renewable energy tend to leave an impression that it can fully substitute our current reliance on fossil fuels. But that is neither possible (due to physical and technical obstacles of renewable energy production) nor sustainable (as producing renewable energy still requires non-renewable resources, such as minerals). A just and equitable energy transition for the people and the planet, requires us to think beyond the realm of industrial capitalism, as no “planet-friendly” energy system can sustain the current need for exponential growth. The implementation of and advocacy for renewable energy by organizations presented in this section goes in tandem with the principles of Energy Democracy highlighted in the first Solution.

Organizations & campaigns leading the way in Renewable Energy:

Sacred Earth Solar

Sacred Earth Solar empowers front line Indigenous communities in Canada with renewable energy.- Piitapan Solar Project - a 20.8kW renewable energy installation in Little Buffalo that powers the community health centre launched by Sacred Earth Solar in 2015. The 80-panel solar project has created more green jobs and reduced the community’s reliance on fossil fuels.

- Sacred Earth Solar - Protecting Land is Protecting Women Video

Post Carbon Institute

Post Carbon Institute’s work in relation to Energy focuses on growing a collective understanding of our energy reality, and the need for both conservation and appropriate, community-centric renewable energy.Green New Deal

The Green New Deal is a congressional resolution that lays out a grand plan for tackling climate change, calling for state- based solutions. While throughout each sector presented by Climate Resource Hub, we highly encourage to step away from state-based solution, due to complexity of the global energy network, some level of state intervention is required to not only leave fossil fuels in the ground and halt any further expansion, but also to lift up highly resource intensive alternative energy projects.- The GND as submitted to US House of Representatives

- Climate Justice Alliance & The Green New Deal: A Green New Deal Must Be Rooted in a Just Transition for Workers and Communities most impacted by Climate Change

- Indigenous Environmental Network responded to the Green New Deal framework by highlighting that any GND Must be rooted in the Indigenous Principles of Just Transition

- IEN’s response to the GND resolution that voices concerns around how it leaves incentives by industries and governments to continue causing harm to Indigenous communities

8th Fire Solar

8th Fire Solar is building a better future for our Native American communities by creating and assembling a sustainable and renewable energy product: solar thermal panels.Solar Bear

Solar Bear is the only Native American owned full service solar installation company in the state of Minnesota that builds renewable energy projects for the future generations of Turtle Island and Mother Earth.Kara Solar

Kara Solar is a solar-powered river transportation, energy, and community enterprise initiative in the Ecuadorian Amazon. This sort of initiative is important as it strengthens indigenous sovereignty and land rights, thereby funding these types of projects enhances the resiliency of the Amazonia rainforest and lowers dependency on fossil fuels in that region.- Conceived in a dream, new solar canoe will serve Amazon tribe

- Here comes the sun canoe, as Amazonians take on Big Oil

More Renewable Energy Resources:

Books, Articles, and Reports

- Resilience.org, Energy Section

- Power for the People: Delivering on the Promise of Decentralized, Community-Controlled Renewable Energy Access, WEDO

- Ordinary Citizens Help Drive Spread of Solar Power in Chile - Inter Press Service

- Another Energy Is Possible, Heinrich Boll Foundation

- Our Power: Achieving a Just Energy Transition for South Africa, AIDC, TNI, TUED

- Community Choice Energy, Local Clean Energy Alliance

Who’s In The Way

Who’s In The Way

Obstacle 1:

Fossil fuel Industry

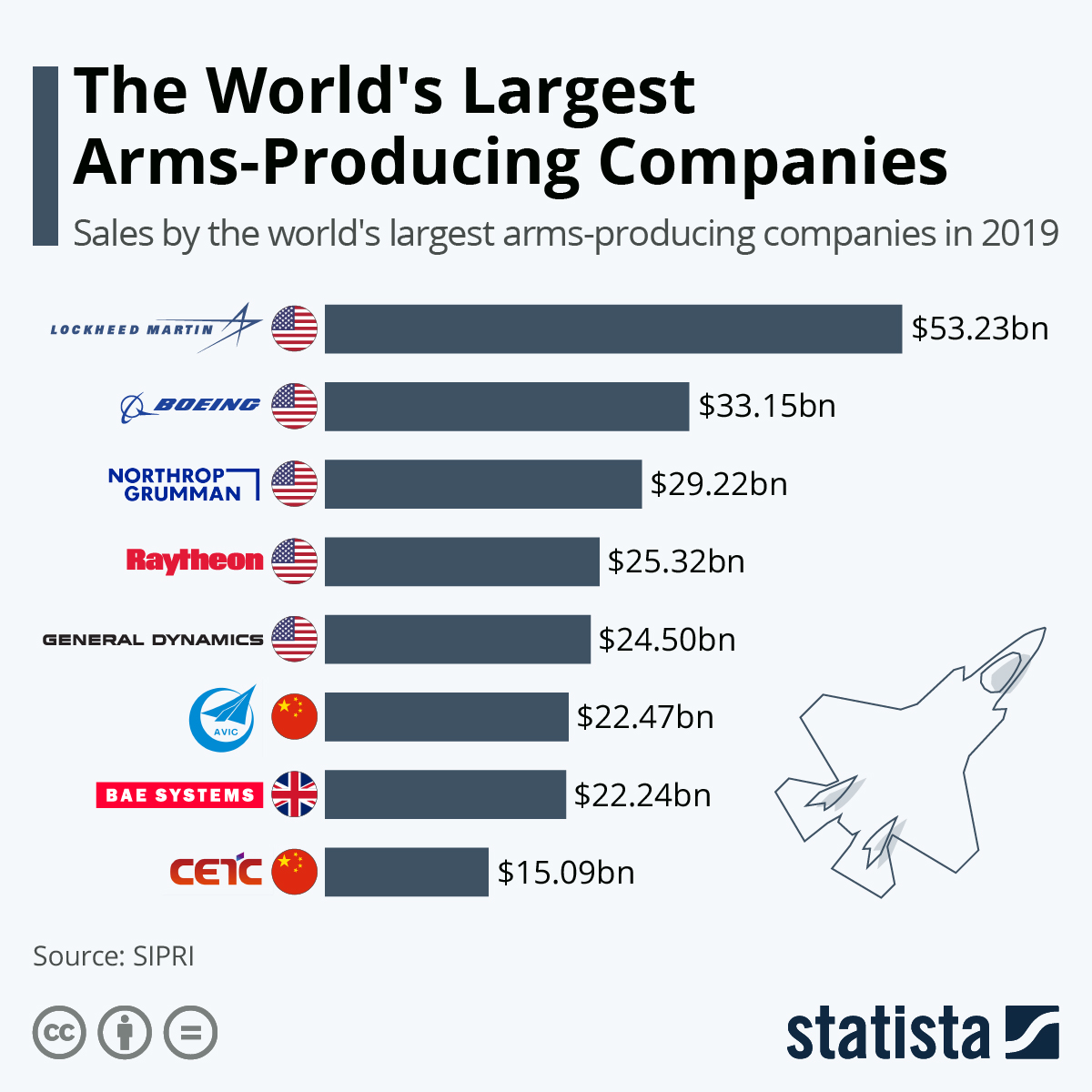

The Fossil fuel industry is the bedrock of capitalism. Big Oil companies have known about the destruction that burning fossil fuels wrecks on the planet for decades, but hid the truth for as long as possible. Now, that the planetary devastation caused by fossil fuels has become common knowledge, the energy sector continues to act despite that truth because they can. Transitioning away from fossil fuels requires a fundamental change in society, so the global political forces that are comfortable within the capitalist status quo are letting the fossil fuel industry continue the planetary destruction, while quickly and effectively enriching themselves and those who allow the extraction to continue. Analysis by Oil Change International demonstrated that G20 countries spend $444 billion per year in subsidies to oil, gas, and coal production - government backing of the fossil fuel sector around the world is one the main reason the industry survives to this day. Keeping fossil fuels in the ground, particularly given how increasingly destructive the methods of extraction have become as we continue to exhaust the resources, is a fundamental step of energy justice work.

"Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Site" by Green Fire Productions is licensed under CC BY 2.0

"Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Site" by Green Fire Productions is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Who’s Working on Dismantling the Fossil Fuel Industry:

Oilwatch

Oilwatch is a network of resistance to the impacts of fossil fuels (oil, gas and coal) industries on people’s and their environments.- Oilwatch Worldwide, News & Campaigns

- Oilwatch Africa 2019 Declaration: Stop the Extractivist Addiction

- Keep Oil Underground: A report by Oilwatch with case studies from the Global South

- Links to organizations organizing against fossil fuel destruction around the world

Oil Change International

OCI works to expose the true costs of fossil fuels and facilitate the ongoing transition to clean energy.- Stop Funding Fossil Fuels Program uses critical analysis and strategic organizing to end the vast quantities of government support flowing to the fossil fuel industry and accelerate the clean energy transition.

- Still Digging: G20 Governments Continue to Finance the Climate Crisis: The report finds that since the Paris Agreement, G20 countries have acted directly counter to it by providing at least USD 77 billion a year in finance for oil, gas, and coal projects through their public finance institutions.

Treaty Alliance to Stop Tar Sands Expansion

This Treaty is an expression of Indigenous Law prohibiting the piplines/trains/tankers that will fuel the expansion of the Alberta Tar Sands

Stop the Money Pipeline

Stop the Money Pipeline is a campaign targeting the financial sector’s support of the cliamte crisis- Rainforest Action Network Campaign: JPMorgan Chase Defund Climate Change

- Liberty Mutual: Ditch Fossil Fuels!

- BlackRock’s Big Problem: Campaign targeting asset managers to stop driving climate change

- DivestED : National training and strategy hub for student fossil fuel divestment campaigns.

- Sign the pledge to divest in the next year - put your money where your solidarity is (organized by Mazaska Talks)

More resources on dismantling the fossil fuel industry:

Reports:

- Towards a Post-Oil Civilization: Yasunization and other initiatives to leave fossil fuels in the soil, EJOLT

- Banking on Climate Change 2020: Fossil Fuel Finance Report Card, RAN

- Drilling Towards Disaster: Why U.S. Oil and Gas Expansion Is Incompatible with Climate Limits, Oil Change International (OCI)

- Burning the Gas ‘Bridge Fuel’ Myth: Why Gas Is Not Clean, Cheap, or Necessary, OCI

- Building a Post Petroleum Nigeria (Leave new oil in the soil), a Proposal by Friends of the Earth Nigeria & Environmental Rights Action

- Oil, Gas and Climate: An Analysis of Oil and Gas Industry Plans for Expansion and Compatibility with Global Emission Limits, CIEL

Campaign:

- Pledge to Divest, Mazaska Talks

Obstacle 2

Mineral Extractivism

"The Mine... Another Look" by Storm Crypt is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

"The Mine... Another Look" by Storm Crypt is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Mining for minerals has a similar record to fossil fuel extraction in terms of the egregious human rights violations and environmental devastation. Minerals are used in everything from our smartphones and jewelry to electrical wiring and fertilizers - and, similarly to oil, the more we deprive this nonrenewable resource, the more destructive the methods of extraction become.

It is crucial to draw attention to mineral extractivism when discussing a Just Energy Transition. An important element to consider in fighting for a transition towards renewable energy are the non-renewable inputs required to produce that energy. Minerals, particularly rare earth elements, are essential to the production of renewable energy, from solar panels to wind turbines and batteries. Many of the key minerals critical to renewable energy production are already scarce and have a history of violence and even slave labor associated with their production. Besides, as analysis by EarthWorks shows “The skyrocketing demand for these minerals is driving the expansion of mining in geographic “hotspots” throughout the world – and even to the depths of the ocean – with disproportionately negative impacts in the Global South.”

The necessity of nonrenewable resources - commonly devastating to both communities and the planet, especially when produced at a large industrial scale - in renewable energy against points to the dire need to actually decrease and localize energy and mineral demand.

Below are examples of communities successfully transitioning out of extractivist mining economy, as well as organizations advocating for people and places affected by skyrocketing mineral demands.

Yes to Life, No To Mining (YLNM)

YLNM is a global solidarity network of and for communities, organisations and networks who are standing up for their Right to Say No to mining and advancing life-sustaining, post-extractive alternatives. In collaboration with the Gaia Foundation, YNLM launched a series of Emblematic Case studies from communities around the world that have been successfully resisting destructive mining.- Myanmar Case Study: A collective from the Karen Environment and Social Action Network (KESAN) describe the Indigenous Karen People’s connection to their ancestral territory, and how they created the Salween Peace Park to assert their right to self-determination and protect their lands from militarism, mining and mega-dams.

- Cajamarca, Colombia Case Study: A study of how farmers, youth and other environmental defenders from Cajamarca, Colombia, have stopped a vast gold mine, re-valued the ‘true treasures’ in their territory and begun to develop regenerative alternatives to mining ‘development’.

- Galiza Case Study (Regenerating the Commons): Joám Evans Pim, villager in the Frojám Community Conserved Area and activist in Galician anti-mining network ContraMINAcción, explains how small communities like Frojám are confronting destructive mining by regenerating community governance and traditional territories.

Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade (EJOLT)

EJOLT looks at mining conflicts and waste disposal conflicts to study the links between increased metabolism of the economy and environmental damage.EJOLT notes following organizations working against mineral extractivism:

Mines and Communities (MAC)

The MAC website seeks to exposes the social, economic, and environmental impacts of mining, particularly as they affect Indigenous and land-based peoples.Mines, Minerals and People

MM&P is a growing alliance of individuals, institutions and communities who are concerned and affected by mining. The isolated struggles of different groups have led us to form into broad a national alliance for combating the destructive nature of mining.Mining Justice Alliance

MJA is a coalition of activists, civil society organizations, students, and community members who initially formed to mobilize around Gorldcorp’s 2011 Annual General Meeting. Our focus has expanded in response to widespread concerns about endemic injustice within Canada’s state-supported mining industry.MiningWatch Canda:

MiningWatch Canada works in solidarity with Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous communities who are dealing with potential or actual industrial mining operations that affect their lives and territories, or with the legacy of closed mines, as well as with mineworkers and former workers seeking safe working conditions and fair treatment.Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros en América Latina (OCMAL) [ES]

OCMAL’s main objective is the defense of the communities and peoples that are impacted by the effects of mining in the region.More Reading Materials:

- Performing ‘blue degrowth’: critiquing seabed mining in Papua New Guinea through creative practice by John Childs

- Extracted: How the Quest for Mineral Wealth Is Plundering the Planet by Ugo Bardi

- The Geopolitics of Mineral Resources for Renewable Energy Technologies by Marjolein de Ridder

- Responsible Mineral Sourcing for Renewable Energy by EarthWorks

- Report: Going 100% renewable power means a lot of dirty mining, Grist

- FACT SHEET: Battery Minerals for the Clean Energy Transition, EarthWorks

False Solutions

False Solution 1:

False “Renewables”

What gets listed under the “renewable energy” umbrella can vary greatly depending on the politics of who’s presenting. For instance, the majority of the “green” corporate sector highlights that energy transition is not possible without the use of nuclear energy, biofuels, and mega-dams. While that point is not entirely untrue, the necessity of these alternatives are entirely based on the desire to hold on to the extractive neoliberal capitalist system that brought us to this crisis in the first place. What proponents of such large scale industrial energy alternatives focus on is their “carbon neutral” footprint while failing to mention just how dangerous and destructive mega dams, nuclear energy, biofuels and incinerators are to planetary and community health. Such high-cost large scale projects also go in opposition to the principles of Energy Democracy and are not meant to benefit communities directly but rather serve as a substitute for profits currently made in the fossil fuel industry,

Below is a short list of false “renewables” and cooresponding organizations working to resist their negative impacts on their communities:

Nuclear Energy

As pointed out by Friends of the Earth International, “Nuclear power is a highly dangerous, high-cost energy source which poses the threat of nuclear proliferation and a severe risk to human life and the environment. Its potential as a major source of destruction has been clearly and repeatedly demonstrated.”Friends of the Earth International:

FoE’s nuclear campaign works to reduce risks for people and the environment by supporting efforts to close existing nuclear reactors and fighting proposals to design and build new ones.

Mega-dams

Large-scale hydroelectric dam projects (aka mega-dams) drive extinction of species, massive displacements of entire villages, flood forests and wetlands, and are thus not a viable strategy for a Just energy Transition. (Read more about the injustices perpetrated by mega-dam projects on our Water page)International Rivers is part of the global struggle to protect rivers and the rights of communities that depend on them.

- 10 Things you Should Know About Dams

- Problems with Big Dams [Video]

- Learn more about Dams & water justice issues on our Water sector page

"Three Gorges dam" by hughrocks is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

"Three Gorges dam" by hughrocks is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Biofuels

Growing biomass requires vast amounts of precious farm and forest land in order to produce a tiny fraction of energy (read more on why monocrops and the industrial agriculture system are deeply damaging to the soil and entire ecosystems on our Food page).Biofuel Watch provides information, advocacy and campaigning in relation to the climate, environmental, human rights and public health impacts of large-scale industrial bioenergy.

Incineration

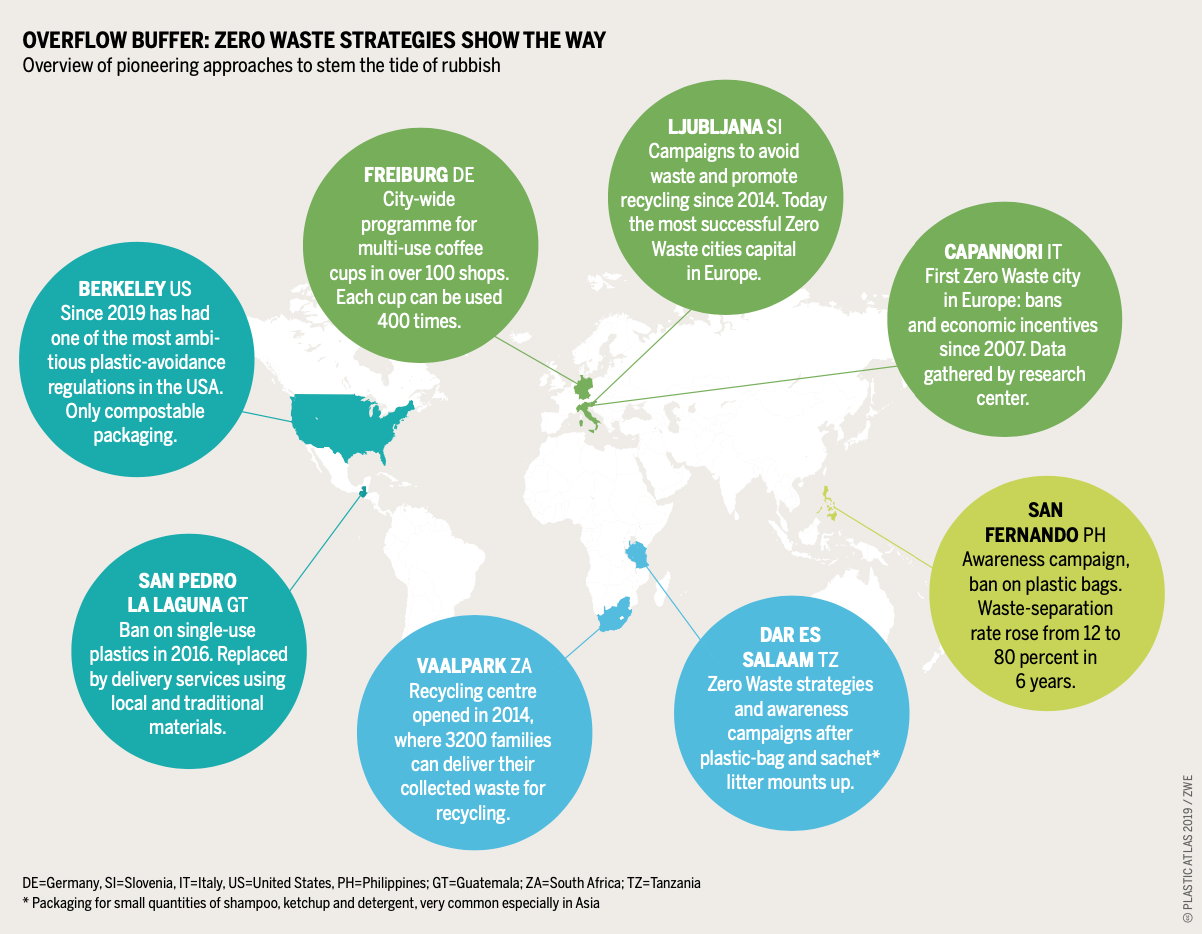

There is nothing “renewable” about burning waste that took many precious resources to produce in the first place. Moreover, incineration is incredibly dangerous as it releases high quantities of toxic air and water pollutants and threatens public health of communities living in proximity to incinerators, which are disproportionately low income and communities of color.Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives: GAIA aims to catalyze a global shift towards environmental justice by strengthening grassroots social movements that advance solutions to waste and pollution. GAIA envisions a just, zero waste world built on respect for ecological limits and community rights, where people are free from the burden of toxic pollution, and resources are sustainably conserved, not burned or dumped.

More reading resources:

- U.S. Municipal Solid Waste Incinerators: An Industry in Decline, TEDC

- “Waste-to-Energy” has no place in Africa, GAIA

- Facts about “Waste-to-Energy” Incinerators, GAIA

False Solution 2:

Carbon Pricing

Carbon Pricing privatizes the air we breathe, turning our atmosphere into something that can be traded on the private market, allowing polluters to continue polluting and poisoning fenceline environmental justice communities.

Who’s Working on Dismantling/Resisting Carbon Pricing:

Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN)

IEN is an alliance of Indigenous peoples whose mission it is to protect the sacredness of Earth Mother from contamination and exploitation by strengthening, maintaining and respecting Indigenous teachings and natural laws.  "Indigenous Environmental Network leaders interrupt President Obama - Oct. 27, 2011" by350.org is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

"Indigenous Environmental Network leaders interrupt President Obama - Oct. 27, 2011" by350.org is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0Climate Justice Alliance (CJA)

CJA is an alliance of over 70 community organizations, movement networks, and support organizations on the frontlines of the climate crisis in North America.- Carbon Pricing Toolkit (collaboration between IEN & CJA)- part of a wider education initiative that aims to build popular education and resistance to carbon pricing from the ground up.

- Carbon Pricing: A Popular Education Toolkit for Community Resistance (by Climate Justice Alliance)

More resources on Carbon Pricing:

Books, Articles, and Papers:

- Carbon Capitalism: Energy, Social Reproduction and World Order by Tim di Muzio

- Energy transitions and the global land rush: Ultimate drivers and persistent consequences, by Arnim Scheidel & Alevgul H. Sorman

- Failing States, Collapsing Systems: BioPhysical Triggers of Political Violence by Nafeez Ahmed

- Indigenous ExtrACTIVISM in Boreal Canada: Colonial legacies, contemporary struggles and sovereign futures by AJ Willow

- Think fossil fuels are bad? Nuclear energy is even worse, MarketWatch

- The Capitalocene Part I: On the Nature & Origins of Our Ecological Crisis by Jason W. Moore

Campaigns & Statements:

- Nuclear Energy Cannot be Considered Renewable Energy, Indigenous Environmental Network

Videos:

Overview

Food and agriculture are often at the center of struggles regarding climate change, capitalism, poverty, and Indigenous struggles. The Indigenous and peasant communities are leading the way in sustainable, just, and equitable paths to food and agriculture.

Despite the industrial food web using up the most resources and producing the most emissions, they only actually produce ~30% of the world's food. Indigenous and peasant communities keep the world fed sustainably by only using a fraction of the resources to produce ~70% of the world's food.

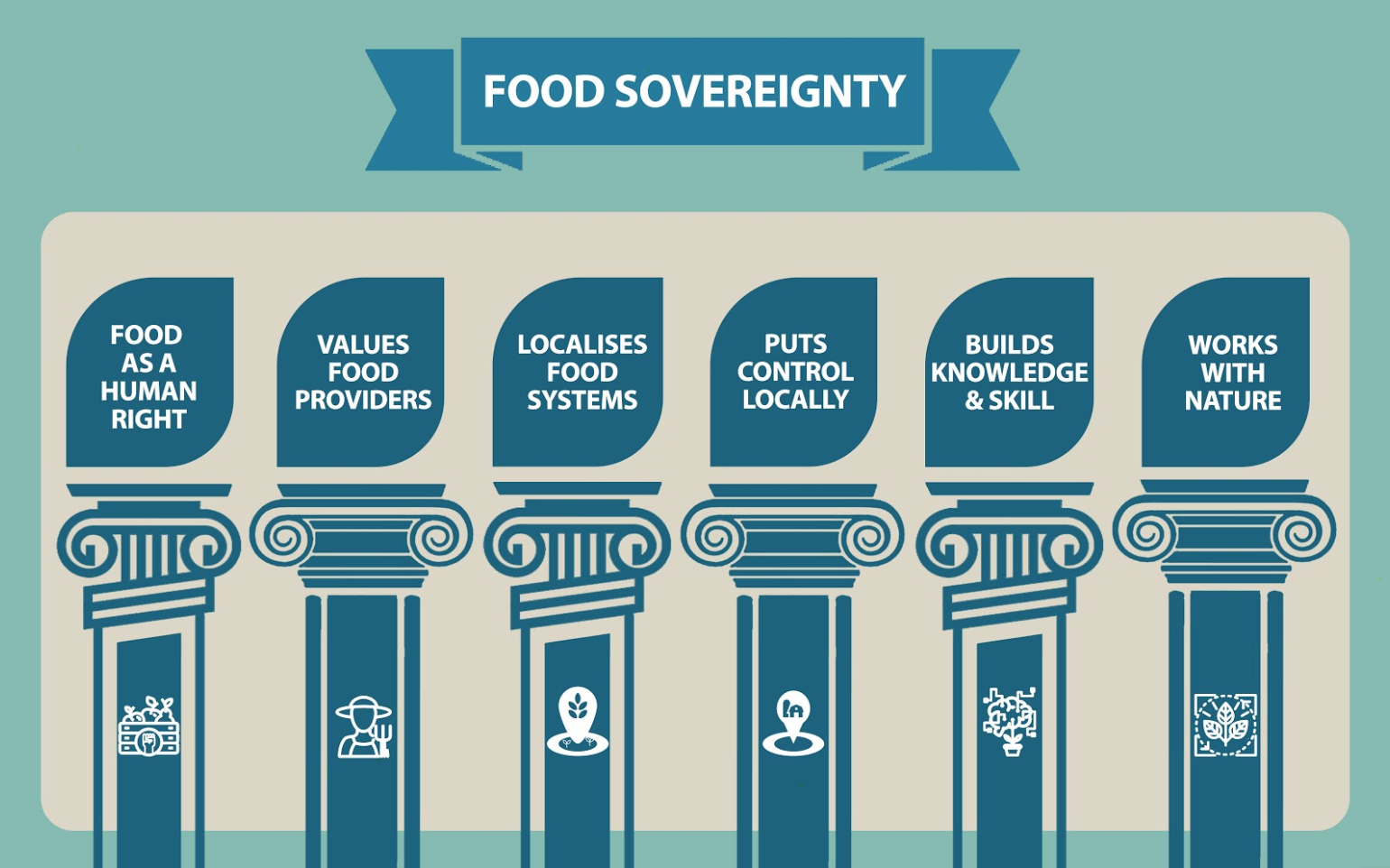

Ensuring an equitable future for our food systems requires a global paradigm shift, away from industrialized agriculture towards regenerative, resilient, and just food systems grounded in Food Sovereignty.

Food sovereignty goes far beyond just providing food for everyone. It values cultural diversity, biodiversity, traditional knowledge, and addresses social justice and environmental degradation. Food sovereignty uses social mobilization to address massive widespread rural disintegration while also addressing the pressing issue of climate change. It aims to focus social and political actions on communities to promote local mobilization and cooperation on a regional, as well as on a much broader, geographic scale.

As a concept, food sovereignty was put forward at an international level by La Via Campesina at the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s World Food Summit in 1996. In this summit LVC presented a set of mutually supportive principles that can ground local and global transitions towards an alternative just food system:

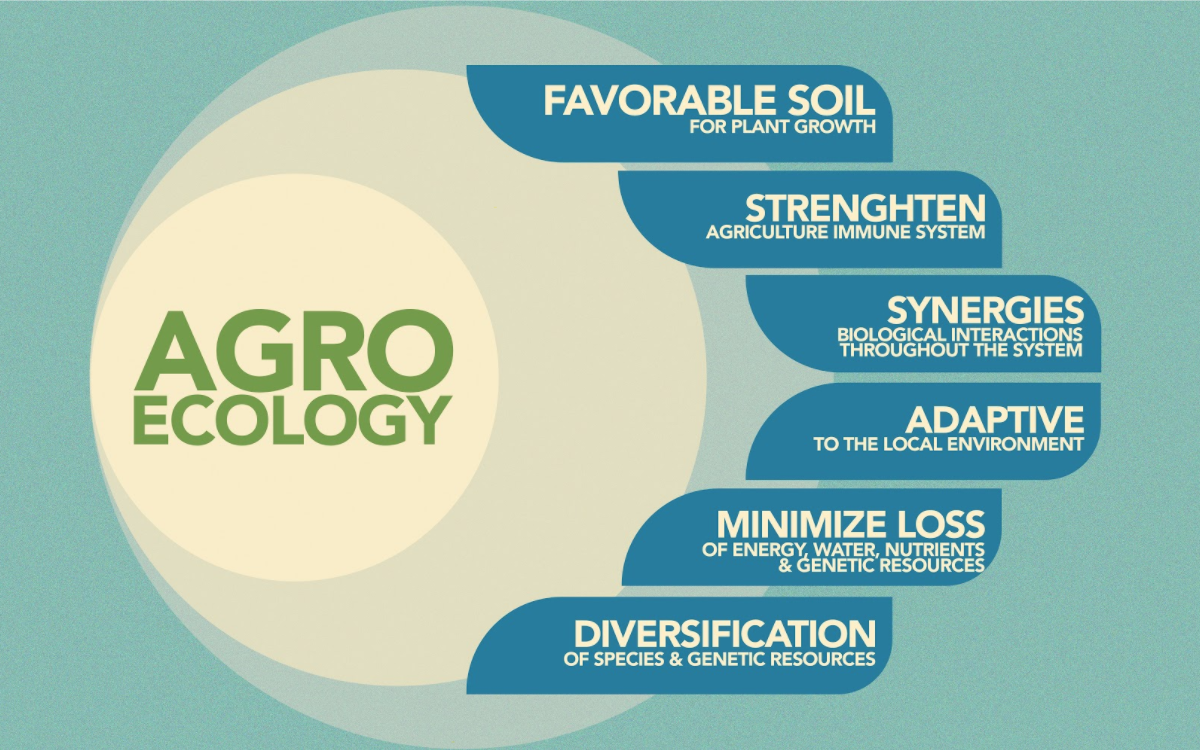

Source: Altieri, M. A., Nicholls, C. I., Henao, A., & Lana, M. A. (2015). Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agronomy for sustainable development. Design and edit by Christian Tandazo.

This section will provide resources to understand the role that capitalism and industrial agricultural actors have in exacerbating climate change, world hunger, Indigenous oppression, and exploitation of labor, as well as resources from frontline communities that fight against the injustices surrounding food and agriculture by either direct action or by serving as models of alternatives.

Way Forward

Way Forward 1:

Agroecology:

Agroecology centers the regeneration of the land while providing food, medicine, and other community needs. It is simultaneously focused on biodiversity and cultural diversity, as the two are inextricably linked. There are a vast range of agroecology projects, as each are localized to the needs of their community, human, water, animal, plant, and geological communities included.

Agroecology is the opposite of industrial agriculture. It is a holistic land-based approach to farming practices, knowledge that has been produced and conserved by peasant, Indigenous, and small-scale family farmers around the world.

Source: Altieri, M. A., Nicholls, C. I., Henao, A., & Lana, M. A. (2015). Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agronomy for sustainable development. Design and edit by Christian Tandazo.

Source: Altieri, M. A., Nicholls, C. I., Henao, A., & Lana, M. A. (2015). Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agronomy for sustainable development. Design and edit by Christian Tandazo.

The knowledge of Peasant and Indigenous farmers is the key component in the design of agroecological farming practices. This knowledge is place-based, locally-adapted, and culturally-relevant, which has been passed down through generations. Industrial agriculture poses a threat to this knowledge. Farm land expropriation by agribusiness and transnational corporations continue to displace peasant and Indigenous farmers from their traditional territories, through this process incredible ancestral agricultural knowledge is lost.

(For more on Peasant Right’s please see “Way Forward 5”)

Agroecology small-scale family farming in Catacocha, Loja, Ecuador. Photo Credit: Christian Tandazo

Agroecology small-scale family farming in Catacocha, Loja, Ecuador. Photo Credit: Christian TandazoAs farm management practice, agroecology would: drastically reduce the use of fossil fuels for chemical and synthetic fertilizers, and pesticide production used in conventional agriculture; potential to mitigate through soil and plant rejuvenation for carbon sequestration; stormwater filtration; has the flexibility and diversity required to allow adaptation for changing climate conditions; and ensure food security.

Some of the multiple benefits of Agroecology include:

- Provide stable yields and tackle hunger: agroecological systems chieve more stable levels of total yield per unit area.

- Linking food to territories

- Nutrition, health and sustainable livelihoods

- Preservation and sharing of cultural diversity and knowledge

- Transparency and access to information

- Central role of rural women

- Restoring ecosystems, soil health, and preserving biodiversity

- Preservation and renewal of genetic resources.

- Harnessing food systems to stop climate change

- Resilience to conflict and environmental disasters.

Agroecology requires we partake in a global paradigm change in our social, political, economic, and cultural relations and structures, but most importantly a change in the relationship between nature and society.

As the climate crisis increases the uncertainty of raising temperatures, intense storm patterns, droughts, and recently the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative we transition from industrial agriculture towards agroecology and food sovereignty. Agroecology is the only model capable of feeding millions of people and addressing the climate crisis, however, this can only be achieved under the leadership of its protagonists: Indigenous, peasant, and small-scale family farmers.

Organizations leading the way in Agroecology:

Black Earth Farms Collective (USA)

Black Earch Farms Collective is composed of skilled Pan-African and Pan-Indigenous peoples who study and spread ancestral knowledge and contemporary agroecological practices to train community members to build collectivized, autonomous, and chemical free food systems in urban and peri-urban environments throughout the Occupied Karkin Ohlone & Chochenyo Territory.Asociación ANDES (Peru):

A Quechua organization that promotes the rights of Indigenous peoples and the biodiversity of food and agricultural systems. ANDES works to support Indigenous peoples through independent research and analysis, strategies based on the development of collective biocultural heritage, networking at the local, regional and international levels, and the promotion of new forms of cooperation and alliances.Soul Fire Farm Inc. (USA):

A BIPOC-centered community farm committed to ending racism and injustice in the food system. With deep reverence for the land and wisdom of our ancestors, we work to reclaim our collective right to belong to the earth and to have agency in the food system. Universidad Ixil (Guatemala)

This University challenges western educational models. The university prioritises oral tradition over written and within its curriculum, promotes the ancestral knowledge born of that same land. Students engage in extensive fieldwork and research in their own communities, with the elders and Indigenous authorities as their principal sources of information.Focus on the Global South (Global)

Focus on the Global South is an activist think tank in Asia providing analysis and building alternatives for just social, economic and political change. One of the issues they cover is Food Sovereignty and Agroecology. Organización Boricuá de Agricultura Ecológica de Puerto Rico

Organización Boricuá, a member organization of La Via Campesina is a grassroots organization that was founded 30 years ago and is one of the leaders of the agroecology movement in Puerto Rico working to connect, teach, and support farmers and spread the use of agroecology across the country.Proyecto Agroecológico El Josco Bravo

Josco Bravo is an agro-ecological production and education project located in the foothills of the town of Toa Alta, Puerto Rico.More Resources on Agroecology:

Books, Articles, and Reports:- Asociación ANDES Knowledge Portal

- BIPOC Led Gardening Projects

- Duru, Michel, Olivier Therond, and M’hand Fares. 2015. “Designing Agroecological Transitions; A Review.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35(4): 1237–57

- Farming While Black by Leah Penniman

- Friends of the Earth International. 2018. “Agroecology: Innovating for Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems”. Who Benefits? Series. 1-32.

- Figueroa-Helland, L., Thomas, C., and Pérez Aguilera, A.. (2018). “Decolonizing Food Systems: Food Sovereignty, Indigenous Revitalization, and Agroecology as Counter-Hegemonic Movements.”

- Food & Land Sovereignty Resource List for COVID-19

- Gliessman, Stephen M. (2008). “Agroecology and Agroecosystems.” In Sustainable Agriculture and Food, Agriculture and the Environment, London: Earthscan.

- IPES-Food. (2018). Breaking Away from Industrial Food and Farming Systems Seven: case studies of agroecological transition.

- IPES-Food. (2016). From Uniformity to Diversity: A paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems.

- Ixil University and the Decolonization of Knowledge by Giovanni Batz

- World Forum of Fisher Peoples. 2017. “Agroecology and Food Sovereignty in Small Scale Fisheries”. Transnational Institute.

- Roces, Irene García, Marta Soler Montiel and Assumpta Sabuco i Cantó. 2014 “Perspectiva ecofeminista de la Soberanía Alimentaria: La Red de Agroecología en la Comunidad Moreno Maia en la Amazonía brasileña.”

Way Forward 2:

Indigenous Forest Gardens

Indigenous Forest Gardens, Forest Garden Systems, and Sacred Forests are highly biodiverse and sustainable agroforestry systems which have been cultivated and nurtured by indigenous peoples.

Forest Gardens are based in polyculture, symbiotic plant relationships, cycles of forest and plant growth, a cosmology of the land as sacred, and traditional ecological knowledge and practices that have been passed down through generations.

The Mayan Milpa system is practiced by most rainforest populations close to the equator, the most densely biodiverse areas in the world today and the locations at highest risk for biopiracy and extractivism. Milpa systems run over cycles of time, not singular farming seasons. Traditionally the cycle might be anywhere from 30 to 50 years, with over 1300 species throughout a given cycle.

These systems include agroecological methods such as partial burns to enhance plant growth followed by the introduction of small crops such as maize. Indigenous forest gardens not only have been proven to increase forest biodiversity, but give communities and towns food sovereignty.

Forest garden systems are used around the world; in India, over 100,000 sacred forests exist. Forest gardens and sacred forests have a high number of medicinal plants and higher species diversity than surrounding forests and even government-protected forestland. Nowadays, the Milpa exists in addition to the home garden and a middle distance garden.

Forest gardens are but one example of agroecology and are based in indigenous cosmologies that surround the sacredness of the land. As many of these practices have been decimated over time through settler colonialism, indigenous led initiatives such as the Zapatista Food Forest, are working on ways to recover, teach, and preserve indigenous knowledge and practices.

Organizations leading the way in Indigenous Forest Gardens:

MesoAmerican Research Center:

The MesoAmerican Research Center seeks to develop a broad understanding of the people, cultures, and environment of the greater Mesoamerican region of Mexico and Central America. Research of the center has emerged in the context of Anthropology and Archaeology, yet is wholly interdisciplinary in focus. The MesoAmerican Research Center continues to maintain its focus on the Maya forest and the broad fields of study in the region. El Pilar Forest Garden Network (Guatemala)

The El Pilar Forest Garden Network is a group of Maya farmers who are keeping alive Maya cultural traditions, promoting sustainable agriculture, conserving biodiversity in the Maya Forest, and educating the public on the value of their time-honored strategies.Forest Peoples Programme:

The Forest Peoples Programme is a human rights based organization that works with forest peoples globally to secure their rights to land and livelihoods. FPP works to support indigenous organizations and forest peoples in advocating for indigenous forest management and assists with handling outside powers that threaten indigenous land rights.More Resorces on Indigenous Forest Gardens:

- The Maya Forest Garde: Eight Millennia of Sustainable Cultivation of the Tropical Woodlands. By: Anabel Ford and Ronald Nigh

- Barbhuiya, A., U. Sahoo, and K. Upadhyaya. 2016. “Plant Diversity in the Indigenous Home Gardens in the Eastern Himalayan Region of Mizoram, Northeast India.” Economic Botany 70(2): 115–31.

- Campanha, Mônica Matoso et al. 2004. “Growth and Yield of Coffee Plants in Agroforestry and Monoculture Systems in Minas Gerais, Brazil.” Agroforestry Systems 63(1): 75–82

- Gabay, Mónica, and Mahbubul Alam. 2017 "Community Forestry and Its Mitigation Potential in the Anthropocene: The Importance of Land Tenure Governance and the Threat of Privatization." Forest policy and economics, v. 79, pp. 26-35.

- Wartman, Paul & Acker, Rene & Martin, Ralph. (2018). Temperate Agroforestry: How Forest Garden Systems Combined with People-Based Ethics Can Transform Culture. Sustainability. 10. 2246. 10.3390/su10072246.

- Ormsby, Alison & Bhagwat, Shonil. (2010). Sacred Forests of India: A Strong Tradition Of Community-Based Natural Resource Management. Environmental Conservation. 37. 320 - 326. 10.1017/S0376892910000561

- IWGIA, PINGOS. Tanzania Indigenous People Policy Brief: Climate Change Mitigation Strategies and Eviction of Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral lands: The Case of Tanzania

Way Forward 3:

Queer & Trans Liberation / Gender Justice

“Mainstream understandings of botany and ecology have been used to justify violence against queer, trans, indigenous, and people of color; female, disabled, and marginalized bodies. The field of queer ecology seeks to reimagine the natural world in a way that values and affirms all life.” - Moretta Browne, Clare Riesman, and Edgar Xochitl

Queer and Trans Liberation, along side Gender Justice has been put forth as a solution for climate justice by many BIPOC women, trans people, and two spirit leaders because an analysis of gender and the violences it inflicts through patriarchy, homophobia, and transphobia, directly underpins the roots of the climate crisis. As shown in the sections above, food sciences have been deeply influenced by capitalism. Queer ecology rejects hetero-patriarchal science norms and forms of linear understanding.

It’s clear that women, trans people, and two spirit people are disproportionately left on the front lines and bear the brunt of climate change as a convergence of crises. As such, attention and efforts need to be focused on securing their safety, autonomy, and futures – these must be pursued through gender self-determination, and redistribution of resources, not a top down approach.

Furthermore, many BIPOC women, queer people, trans people, and two spirit people have been, and are already building resilient futures out of necessity. Mutual aid efforts around food security, healthcare access, diaster relief, harm reduction and more, are all efforts born from BIPOC queer communities because the system today has never worked for them. When looking towards solutions to building community resiliency that prioritizes agency of us that are most vulnerable, the BIPOC queer community is leading the way.

Organizations leading the way:

Our Climate Voices

Our Climate Voices seeks to make climate change personal through localized and community based storytelling and organizing. They put together a great listening series on the relationship between Climate Justice and Queer and Trans Liberation. La Via Campesina

La Via Campesina, the largest international member based peasant’s movement, prioritizes the needs of women because they see “Food Sovereignty as a feminist issue.” Practices such as Agroecology and food sovereignty promote women’s autonomy as when capitalism and the norms of domination of women by men and men of the earth are abolished, all life becomes safer.- Keeping the Struggles of Peasant Women Alive, La Via Campesina

- Women’s struggles for a Peasant and Peoples’ Feminism

More Resources on Queer & Trans Liberation / Gender Justice:

- Brady, A., Torres, A., & Brown, P. (2019). What the queer community brings to the fight for climate justice.

- Brimm, Katie. (2019) We are Natural: California Farmers Reimagine the World through Queer Ecology

- Kabir, Kareeda. (2018) How Climate Change in Bangladesh Impacts Women and Girls, NYU Press. Queer Ecology

Way Forward 4:

Peasant Rights

Peasants, small scale farmers and fishers, family farmers, pastoralists, hunters and gatherers, have been at the forefront of the fight for food sovereignty against agribusiness and transnational corporations. Unfortunately, taking a stand against corporations has propelled violence agaisnt peasants and workers, as more people continue to be displaced from their traditional farming lands at the hands of agribusinesses and transnational corporations. They have been criminalized or even killed for the simple act of saving seeds to feed their families.

Peasants are safeguards of agrobiodiversity, biocultural diversity, and traditional agricultural knowledge that foster a relationship of reciprocity, with the land, water, soils, non-human kin, and microbial diversity. Peasants also care for seeds, contributing to global seed diversity by protecting and sometimes interbreeding 50,00 - 60,000 wild relatives of cultivated species at no cost.

Through these practices, peasants have become the main or sole food providers to more than 70% of the world’s population, while Industrial Agriculture only feeds 30%. Peasants produce this amount of food with less than 25% of the resources the industrial food system uses - including land, waste, fossil fuels - used to get all of the world’s food to the consumer’s table.

The ancestral knowledge and practices that peasants hold are vital to global food security, provide an opportunity to drastically reduce emissions from the agriculture sector, revitalize depleted soils, preserve biodiversity, and produce healthy and culturally relevant foods.

However, peasants alone won’t be able to solve the world’s crises and threats to food security, therefore, it is imperative to show support for peasants in the fight and struggle for their rights, whether at the policy level or on the ground.

Organizations leading the fight for Peasant’s Rights:

La Via Campesina (LVC)

LVC is the largest transnational agrarian movement today. LVC actively builds alliances with other social movements, bringing together millions of peasants, small and medium size farmers, landless people, rural women and youth, indigenous people, migrants and agricultural workers from around the world; trying to respond to the impacts of capitalist development in food, agriculture and land-use. LVC is mainly recognized for championing and developing the Food Sovereignty paradigmLVC is built on a strong sense of unity, solidarity, it defends peasant, Indigneous and small-scale family farmers for food sovereignty as a way to promote social justice and dignity and strongly opposes corporate driven agriculture that destroys social relations and nature.

- Illustration - UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP)

- The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants: A Tool in the Struggle for our Common Future

Movimiento Campesino a Campesino (MCAC) - (Central America and Cuba)

MCAC, or Farmer to Farmer, is a grassroots movement that originated in the early 1970s in Guatemala and expanded to Mexico, Nicaragua, and Cuba. It was pioneered by Mayan campesinos who applied methods of soil and water conservation in their farming practices. They later proceeded to share this knowledge with other peasant farmers in Mexico. This was has been described as peasant pedagogy, which generates effective site-specific agroecological solutions, encourages forms of non-hierarchical communication and leadership structures. This for of pedagogy was later spread throughout Central America and the Caribbean.The peasant seeds network (France)

The Peasant Seeds Network leads a movement of collectives rooted in the territories which renew, disseminate and defend peasant seeds, as well as the associated know-how and knowledge.These collectives are inventing new seed systems, a source of cultivated biodiversity and autonomy, in the face of the industry's monopoly on seeds and its patented GMOs.

More Resources on Peasant Right’s:

- Bocci, R. & Chable, V. (2009). Peasant seeds in Europe: stakes and prospects.

- ETC Group. (2017). Who Will Feed Us?: The Peasant Food Web vs. The Industrial Food Chain.

- Gevers, C., van Rijswick, H., & Swart, J. (2019) Peasant Seeds in France: Fostering A More Resilient Agriculture

- Rosset, Peter & Sosa, Braulio & Jaime, Adilén & Avila, Rocio. (2011). The Campesino-to-Campesino Agroecology Movement of ANAP in Cuba: Social Process Methodology in the Construction of Sustainable Peasant Agriculture and Food Sovereignty.

Who’s In The Way

Obstacle 1:

Industrial Agriculture

Industrial agriculture (IA) involves huge monoculture farms that prioritize crops for biofuel production rather than produce. These farms pollute local water supplies, erode the soil, and are less resilient to climate disasters due to their lack of crop diversity. This system uses more than 75% of the world’s agricultural land, a process that destroys 75 billion tons of topsoil annually.

It is a linear sequence of links running from production inputs: crop and livestock genomics, pesticides, fertilizers, farm machinery, veterinary medicine, to transportation and storage, then to milling processing and packaging, to consumption outcomes: wholesaling, retailing, restaurants, delivery of home, and food lost and wasted.

Monoculture farms are far less resilient to climate disasters than agroecological farms, leaving IA farmers with no income or produce after climate disasters, such as Hurricane Maria in 2017. They also disconnect consumers from peasants and land, altering our food customs and practices and accelerating the loss of agrodiversity.

Globalized IA is responsible for 50% of global greenhouse gas emissions, one third of which comes from livestock, and accounts for 85-90% of all agricultural emissions. IA requires intensive pesticide and fertilizer use which ruins the soil, chemicalizes the land, water, and crops, and exacerbates the impacts of climate change

In addition, IA uses 70% of all withdrawn water resources and most of it is used for irrigation, livestock – which accounts for 27% of water use, and processing. The use of massive amounts of drinking water in IA threatens the stability of water and food security throughout the globe as food is dependent on water availability.

Over the last 50 years much of the world’s agriculture has been transformed from traditional peasant agriculture into IA from traditional peasant agriculture, simultaneously, in the last 50 years humans have tripled water extraction withdrawing about four thousand cubic kilometers of water globally each year.

The rapid expansion of Industrial Agriculture and globalization of food systems has narrowed the agrobiodiversity world’s food supply, increasing the likelihood of catastrophic crop failure in the event of drought, heavy rains, and outbreaks of pest and disease. We are currently witnessing these catastrophic climate events unfold, such as the wildfires in the worlds’ forests, droughts in farmland, locust swarms in Africa, and the COVID-19 pandemic – all of which have been exacerbated by climate change.

Organizations working to dismantle Industrial Agriculture:

Timbaktu Collective

The Timbaktu Collective, an India-based NGO, aims to enable marginalised rural people, landless labourers, and small and marginal farmers particularly women, children, youth, Dalits and the people with disabilities, to enhance their livelihood resources, get organised and work towards social justice and gender equity and lead life in a meaningful and joyous manner. Organic Farmers in the Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India in 2015

Photo credit: Laura Langner

Organic Farmers in the Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India in 2015

Photo credit: Laura LangnerTheir vision is for rural communities to take control of their own lives, govern themselves and live in social, gender, and ecological harmony while maintaining a sustainable lifestyle.

- Organic Farmer Cooperative Program - Assists farmers in switching from industrial agriculture to organic farming, re-empowering farmers strapped by loans (due to high costs of chemical inputs & monoculture) through the support of the cooperative & knowledge sharing through farmers

- Dharani - Removes the middleman and allows organic cooperative farmers to directly profit from their crops & be economically protected through good/bad seasons. They attempt to engage with the market through a Cooperative model, with larger numbers being a source of strength and solidarity.

Navdanya

Vandana Shiva’s seed saving non-profit which has created 122 community seed banks in India to directly counteract industrial agriculture’s patenting of seeds and allow farmers to regain autonomy. ETC Group

ETC Group addresses the socioeconomic and ecological issues surrounding new technology that impact the world’s marginalized people. They investigate the erosion of ecology, culture, and human rights; monitor global governance issues including corporate control and concentration of technologies; and the development of new technologies, in particularly agricultural but also other technologies. They work closely with partner civil society organizations and social movements, especially in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

More Resources on dismantling Industrial Agriculture:

Books, Articles, and Reports:

- Campbell, B. M., D. J. Beare, E. M. Bennett, J. M. Hall-Spencer, J. S. I. Ingram, F. Jaramillo, R. Ortiz, N. Ramankutty, J. A. Sayer, and D. Shindell. (2017). Agriculture production as a major driver of the Earth system exceeding planetary boundaries

- IPES-Food. 2017. Unravelling the Food–Health Nexus: Addressing practices, political economy, and power relations to build healthier food system

- Jacquet, P. &, & Pachauri, R. K., Tubiana, L. (2012). Towards Agricultural Change? Development, the Environment and Food

Obstacle 2:

Agribusiness, Transnational Corporations (TNCs), & Mega-Mergers

Agribusiness is the business of Industrial Agriculture and plays a role as a global hegemonic power pushing for land and water resource acquisition.

In the last couple of decades agribusiness corporations have been merging at an unprecedented rate. In 2001, six companies were the global leaders: Monsanto, Syngenta, Dupont, Dow Chemical, Bayer CropScience and BASF. These companies became known as the “the big six” and by 2013 they controlled 63% of comercial seed sales globally, and 75% of agricultural chemical sales around the world.

Back in 2016, there were The Big Six & ChemChina:

Then, in 2017, there was a push for further consolidation of monopoly corporatist power with the announcement of three agribusiness mega-mergers: ChemChina-Syngenta, Bayer-Monsanto, and Dow-DuPont. These mergers were approved by industry regulators.

The Big Six were now The Big Four: Bayer-Monsanto, DowDupont/Corteva, ChemChina-Syngenta, BASF.

Later, Dow-Dupont split into three chemical corporations in 2019: Dow, DuPont, and Corteva Agriscience.

Dow focuses on performance chemicals, chemical additives, and packaging. Market cap: $33.5 billion

Dupon focuses on specialty material, high-growth materials, and nutrition. Market cap: $49.6 billion

Corteva Agriscience focuses on agricultural chemicals and seeds. Market cap: $21.8 billion. Derives more than half its revenue from North America.

TNCs are involved at multiple levels of natural resource acquisition and degradation. TNCs have displaced local food retailers and promoted worldwide convergence of urban diet on a narrow range of staple foods as well as meat, edible oils, fats, sugars, and cheap unhealthy processed foods, contributing to the global epidemic of obesity and diet-related diseases.

Some well-known TNCs are*: Sime Darby Bhd, Dole Food Company Inc, Fresh Del Monte Produce, Cargill, Deere & Company, Nestle SA, Unilever, Kraft Foods Inc., Mars Inc., Coca Cola, Suntory Ltd.

*Source: World Investment Report: Transnational Corporations, Agricultural Production and Development.

Agribusiness and TNCs have created monopolies to hold power and control of our food systems. The world can no longer sustain this.

Organizations leading the fight against Agribusiness, Transnational Corporations, and Mega-Mergers:

La Via Campesina (LVC)

As the largest transnational agrarian movement, LVC has been the leader in the fight against agribusiness, TNCs, and extractive industries. They have developed multiple international campaigns to prevent further consolidation of power from corporations.Farmworker Association of Florida

The Farmworker Association of Florida, a member organization of La Via Campesina, focuses on protecting farmworkers and rural poor communities in Florida from the injustices and dangers of working on industrial agriculture farms including continual exposure to pesticides, extremely hot temperatures, and economic and physical exploitation as undocumented migrant workers and the surrounding community. Coalition of Immokalee Workers

This is a worker-based human rights organization internationally recognized for its achievements in fighting human trafficking and gender-based violence at work. - Fair Food Program

- Anti Slavery Program

- Campaign for Fair Food

- Facts and Figures on Florida Farmworkers

More Resources on dismantling Agribusiness, TNCs, and Megamergers:

Books, Articles, and Reports:

- Gonzalez, Carmen. 2016. The Environmental Justice Implications of Biofuels. Los Angeles: UCLA.

- Food and Water Watch. (2020). DOJ Fast Tracking Lethal Agricultural Mega-Mergers

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018).Concentration in Seed Markets: Potential Effects and Policy Responses

- Reuters. (2020). ChemChina, Sinochem merge agricultural assets: Syngenta

- Ribeiro, Silvia. (2020). Breeding the Next Pandemic

- Starbuck, Amanda, C. (2020). Mega-Mergers Are As Guilty As the Pandemic for our broken Food Supply Chain.

- ETC Group & IPES-Food. (2017). Too Big to Feed: Exploring the impacts of mega-mergers, consolidation and concentration of power in the agri-food sector

- Transnational Institute. (2019). Mega-Mergers and the fight for our food system.

Obstacle 3:

International Financial Institutions (IFIs)

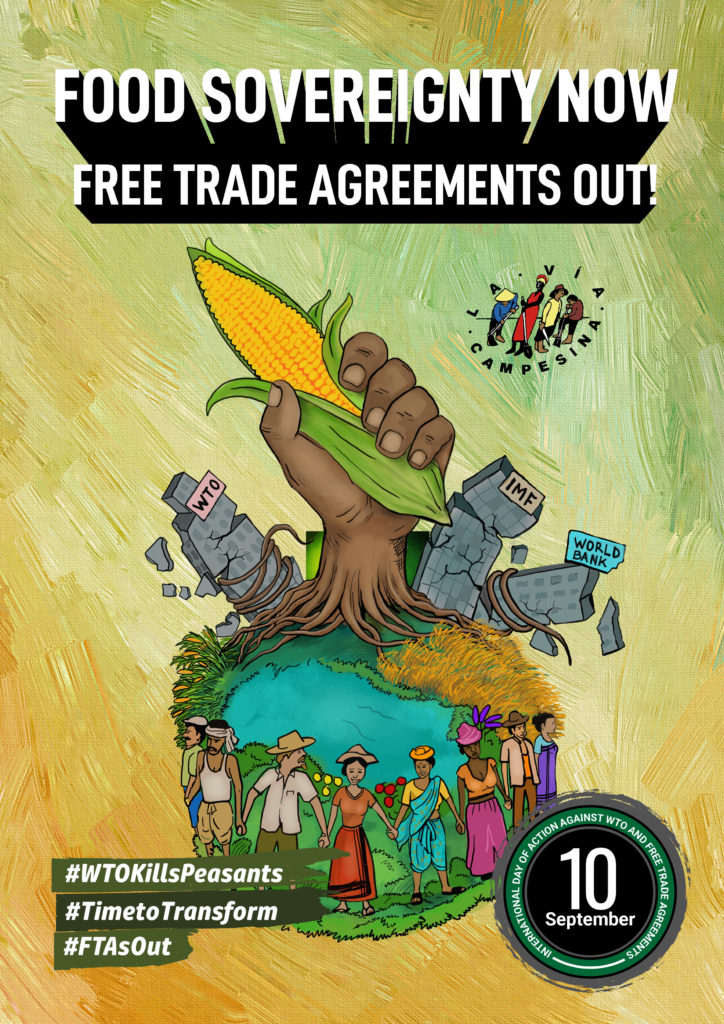

World Trade Organization (WTO)

The WTO Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) contained numerous ambiguities that enabled wealthy nations to subsidize and protect their domestic agricultural sector while constraining the ability for developing nations to utilize tariffs to protect their small farmers from economically devastating surges of cheap food (Gonzalez, 2011).World Bank (WB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF)

In the 1970s the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) pushed developing countries to take out loans from global North banks to pay for imported fuel and petroleum-based agricultural inputs. In 1979-80 oil prices shook while agricultural commodities‘ interest rates soared and prices dropped, making debtor nations in the global South unable to repay their loans (Gonzalez, 2011).The WB and IMF addressed this issue by imposing a structural adjustment (a standard receipt of free market reforms) on these indebted nations that eliminated subsidies to the agricultural sectors, it opened up their markets to foreign competition by reducing tariffs and other trade barriers (Gonzalez, 2011).Structural adjustment introduced a double standard in international agricultural trade that continues to the present day: open markets for the poor and protectionism for the wealthy (Gonzalez, 2011).

Organizations leading the fight against IFIs:

La Via Campesina

LVC is committed to fighting against the manipulation of international financial institutions over our food systems, peasant and land rights.Obstacle 4:

Extractive Industries

Extractive industries such as mining, drilling, and fracking are not only drivers of climate change, but they also have extreme detrimental effects on land and ecosystems, water sources, the air, local food systems and food sovereignty leading to serious repercussions on the livelihoods, health, culture, and economic well-being of local communities, predominantly rural, peasant, and indigenous communities worldwide.Organizations leading the fight against Extractivism:

GRUFIDES (Peru)

Fighting against mining projects in PeruUnist'ot'en camp

Leading the fight to protect unceded territory, rivers, and land from the Coastal Gaslink Pipeline Amazon Frontlines

Defending Indigenous rights to land, life and cultural survival in the Amazon rainforest.False Solutions

False Solutions 1:

Global Redesign Initiative

The Global Redesign Initiative (GRI), spearheaded by the World Economic Forum, is a system of multi-stakeholder governance (MSG) as a partial replacement for intergovernmental decision-making (La Via Campesina, 2016) which encourages the privatization of the governance of people’s food systems and nutrition. Other similar “no-go” solutions that follow the GRI logic are the Scaling-Up Nutrition (SUN), Coastal Fisheries Initiative (CFI) or the G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition for Africa (La Via Campesina, 2016).

False Solution 2:

Agricultural Biotechnology

As the global population grows, agricultural biotechnology, agritech or biotech is frequently seen as a solution to increase global food supply. Global food insecurity is due to lack of proper distribution rather than supply. We currently produce more than enough food to feed the world’s growing population. Biotechnology presents many problems including further corporate control of our food system, negative effects on ecosystems, land degradation, use of chemical inputs, idk if this makes sense my brain is fried genetically modifying crops, contamination of non-GM crops by GM crops, corporate ownership of land for biotech experimentation, and the patenting of seeds and knowledge. While debates exist in the realm of GM foods, the side effects of GMO are still up for debate.

False Solution 3:

Biofuel

Biofuel is fuel created by biomass, plant material, and is seen as an energy solution to climate change creating ethanol or biodiesel. To create biofuel, huge swaths of land are used to grow monoculture crops, meaning this land is not being used to grow food for local communities. The U.S. spends billions of dollars subsidizing biofuels and pouring money into companies such as Monsanto, Shell, Exxon, and Syngenta. Biofuels perpetuate global poverty and exacerbate food insecurity, food price increases, and climate change (Gonzalez, 2016). The EROEI, energy return on energy invested is far too low with biofuel, meaning that it almost takes as much energy to create the fuel that it then creates, making biofuel production an inefficient use of land and a

false climate solution.

(For more inforamtion on Biofuels please refer to the Energy + Minerals section)

False Solution 4:

Climate-smart agriculture

The Global Alliance of Climate Smart Agriculture, launched at the UN in 2014, as a way to continue increasing “farming productivity, build resilience to climate change, and reduce/ remove greenhouse gas emissions.” Disturbingly, out of the 29 forming members of the Alliance, three were fertilizer lobby groups and two were the world’s largest fertilizer companies - groups whose goal is to advance the interest of the agribusiness sector and maintain goal profit-based extractivist food production. Thus, their corporate agenda is now deeply entrenched in Climate Smart Agriculture, making it another false solution bound to create further harms instead of repairing them. CSA is a clear continuation of colonial imperialism and does not offer any real system changes to the food system required in the age of the climate emergency.

More Resources:

-

The Exxons of Agriculture, GRAIN

-

Climate Smart Agriculture Concerns

-

‘Climate-Smart Agriculture’: the Emperor’s New Clothes? CIDSE

Overview

Land is the basis for all life. It is the ground from which our plants grow and water flows. Land shapes and is shaped by societies’ political, economic, and cultural dynamics. Power affects land access, and land access grants power. Given land’s central role to human society, it is unsurprising that land privitization has been central to profit accumulation in the expansion of global capitalism.

![]()

El Salvador, Photo credit: Génesis Abreu

The ongoing legacy of European colonization commodified land as property that can be owned, privatized, and sold while dispossessing the original caretakers and inhabitants of the land. Colonization, capitalism, and the patriarchy have shaped, overused, destroyed, and pillaged the land, causing genocide and decimation of entire peoples and cultures globally, predominantly affecting Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). For Indigenous peoples, land and nature are not merely resources that can be valued monetarily and exploited purely for production and extraction but rather as relatives within one ecosystem.

“Within Indigenous contexts land is not property, as in settler colonialism, but rather land is knowing and knowledge” (Arvin et. al, 2013).

Want to learn more about the history of colonization in the U.S.?

Check out this Interactive Time-Lapse Map that shows how the U.S. stole over 1.5 billion acres from Native Americans.

The Western ideal of land ownership and property rights stands in stark contrast with Indigenous cosmologies, rooted in the symbiotic relationship between humans, plants, animals, and the land. It’s telling that the places on Earth with the greatest biodiversity are the areas with the highest linguistic and cultural diversity, a term researchers have defined as biocultural diversity – through a worldview that is based in reciprocity rather than extractivism, many beings are possible. Indigenous territories make up ~20% of land on Earth; that land holds 80% of the Earth’s biodiversity. Through colonization, Western powers and norms have worked tirelessly to promote one way of relating to the land – dominance – which has proven to be impossibly unsustainable and destructive.

Thus, systemic climate solutions to land are based in decolonization, re-indigenization, land rematriation to BIPOC communities, re-commoning the land, shifting away from the extractive economy to a regenerative economy, and a re-localization of governance as we strengthen communities and move toward alternative and communal forms of caring for and relating to the land.

Costa Rica, Manuel Antonio, Photo credit: Génesis Abreu

Way Forward

Way Forward

Way Forward 1:

Decolonization

“Decolonization brings about the [rematriation] of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools...the increasing number of calls to ‘decolonize our schools,’ or use ‘decolonizing methods,’ or, ‘decolonize student thinking’, turns decolonization into a metaphor.”

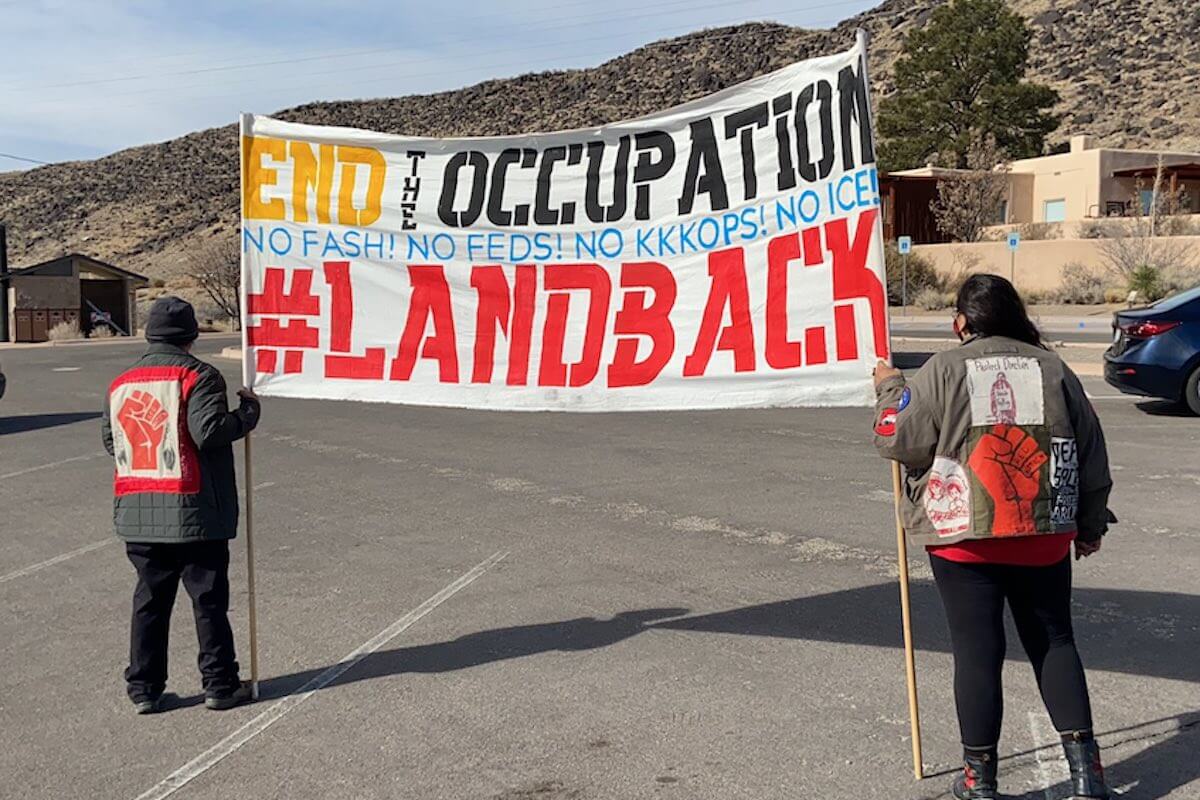

Decolonization first and foremost means land back: the rematriation of land to its original caretakers. Decolonization is rooted in re-Indigenization. Decolonization must take place in conjunction with the transition away from the deadly systems of racial capitalism and patriarchy and toward a regenerative, place-based economy and way of relating to one another and the land.

When discussing issues of decolonization, the true meaning of the word often gets diluted, manipulated, or redefined to avoid the discomfort of its reality. It is often easier for non-Indigenous people to speak metaphorically, whereas true decolonization means the return of land and resources which non-Indigenous folks have benefited from, thus becoming a material loss. In addition, there is usually the support from non-Indigenous allies of decolonization with a qualification included, settler futurity. Settler futurity continues the settler colonial project which burdens Indigenous people with the task of considering the settlers place during and after decolonization despite Indigenous people enduring centuries of violence from settlers. Decolonization is the ACTION of removing colonialism from all aspects of knowledge gathering, and prioritizes LAND.

Want to learn more about Land Back?

Checkout Regan De Loggans‘s Land Back Zine

Contemporarily, the call for decolonization has taken many shapes, some more overtly militant than others. It can include the reclamation of Indigeneity through skill share of their precontact knowledge. But it is inherently tied to the LAND. Indigenous scholar and activist, Nick Estes notes “most people think that decolonization would mean getting kicked off the land, or that Indigenous people would do to them what they did to Indigenous people in the past.” Land back does not mean the colonial replication of exclusionary property ownership. Land back includes rematriation of land, the recognition of Indigenous peoples as land stewards and protectors of the Earth, and Indigenous self-governmence and sovereignty.

It is essential however, to also acknowledge that in decolonial rhetoric, we should not continue to perpetuate anti-Black sentiment and the erasure of Black communities' relationship to land and nature. Therefore, movements of decolonization must also repair or repay the harm, terror, and violence committed against Black people when they were stolen from their ancestral homes to be part of the settler colonial project. Land for Black people can provide autonomous self-determination that is rooted in healing and reconnection to Mother Earth.

Want to learn more about how decolonization is tied to abolition and racial justice?

Checkout this podcast by Nick Estes and Noname.

Decolonization cannot happen overnight, but movements to decolonize have been long underway. Decolonization must be the initial step, but along with decolonization we must shift to localized & regenerative economies, based in systems of care, systems that acknowledge reproductive and domestic labor, systems that are rooted in anti-racism, communal wellness, public health, and connection to the land. Decolonization will not look the same everywhere. However, the future we are calling for is based in community rather than individuality. Without decolonization, we will not have climate justice.

Organizations leading the way:

Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Mexico)

The Zapatistas are an anti-globalization, social and political group and movement based in land sovereignty and autonomy from Chiapas, Mexico. The EZLN has inspired anti-globalization, anarchist, feminist, decolonial, and indigenous movements around the world.Kanatsiohareke Mohawk Community (USA)

Promotes the development of a community based on the traditions, philosophy, and governance of the Haudenosaunee, and to contribute to the preservation of the culture of people as a framework for a blend of traditional native concerns with the best of the emerging new earth friendly, environmental ideologies that run parallel to these traditions.Unist'ot'en Camp - Wet'suwet'en STRONG (Canada)

The Unist’ot’en Camp is a re-occupation of indigenous Wet’suwet’en land in so called B.C., Canada. Unist'ot'en have been taking action to protect unceded land from the RCMP and the Coastal Gas Link Pipeline. Their mission is decolonization and to heal and protect the land and people.Universidad Ixil - Decolonizing Education for Land Sovereignty (Guatemala)

This University challenges western educational models. The university prioritises oral tradition over written and within its curriculum, promotes the ancestral knowledge born of that same land. Students engage in extensive fieldwork and research in their own communities, with the elders and Indigenous authorities as their principal sources of information.Indigenous Environmental Network (USA & Canada)

An alliance of Indigenous peoples whose mission it is to protect the sacredness of Earth Mother from contamination and exploitation by strengthening, maintaining and respecting Indigenous teachings and natural laws.The Ganienkeh Council Fire (USA & Canada)

Ganienkeh is a branch of the original sovereign Kanien’kehà:ka Nation located within the sovereign traditional territory of the Kanien’kehà:kaa independent from those entities of North America referred to as the United States of America and CanadaIndigenous Kinship Collective (USA)

A community of Indigenous womxn, femmes, and gender non conforming folx who gather on Lenni Lenape land to honor each other and our relatives through art, activism, education, and representationFurther Resources on Decolonization

Books, Articles, and Reports:

- Standing Rock Syllabus (Education Syllabus)

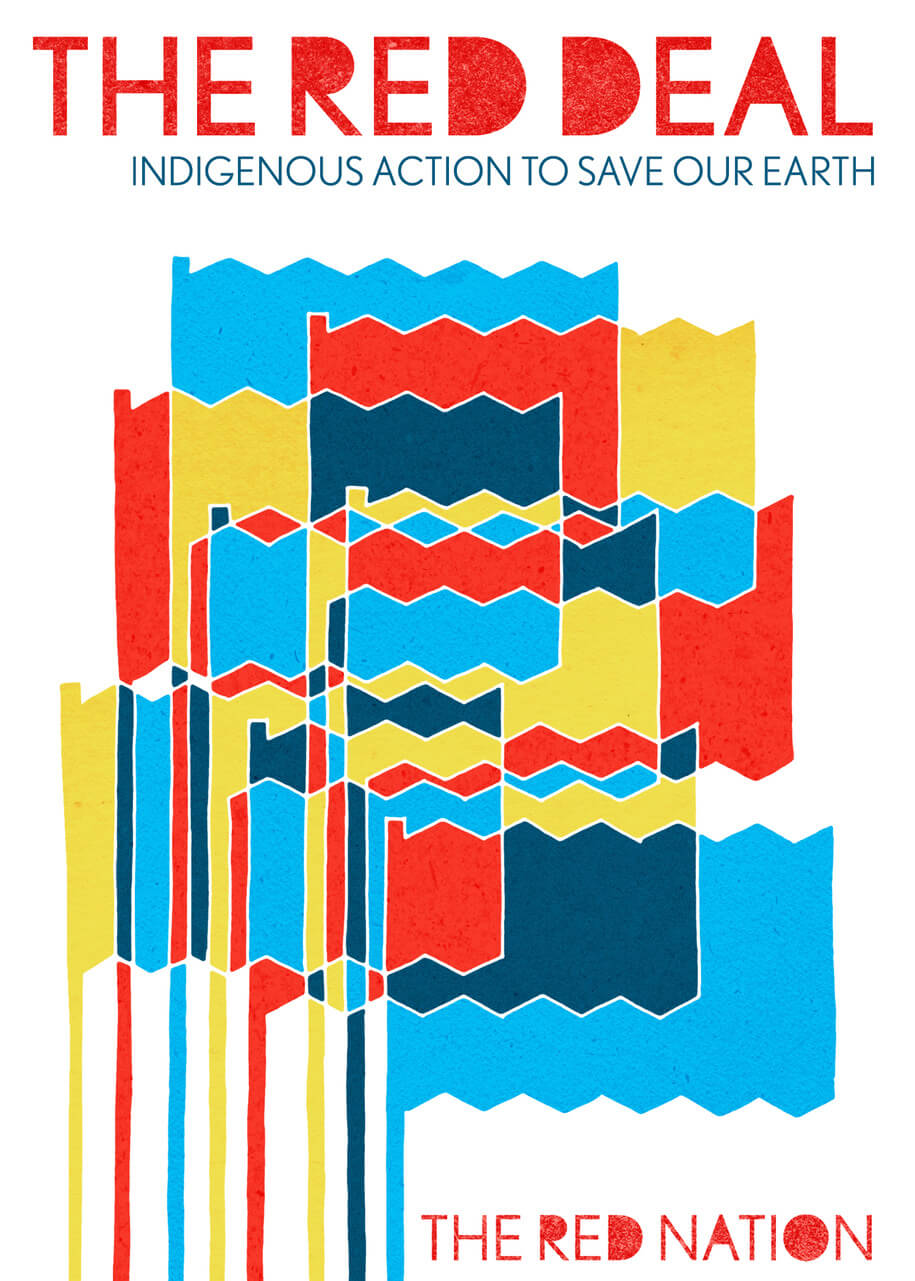

- A Red Deal by Nick Estes

- Fighting for Our Lives: #NoDAPL in Historical Context

- Indigenous Youth Are Building a Climate Justice Movement by Targeting Colonialism by Jaskiran Dhillon

- Revitalization and Indigenous Resistance to Globalization and Neoliberalism by James Fenelon and Thomas Hall

- Decolonization is Not a Metaphor by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang

- Mauna Kea: What it Is, Why it's Happening, and Why we Should All Be Paying Attention

Websites & Media:

Way Forward 2:

Land rematriation; Spatial Reparations for Black, Indigenous, and POC communities

Land is power. Although it provides one of the main wealth accumulation tools, land is essential in the fight for self-determination and liberation for Black and Indigenous communities globally. Conversations about the future of sacred land foster opportunities for reconciliation and reparations with Black, Indigenous, and other historically oppressed communities. For Indigenous peoples, land is not merely a resource with monetary value to be exploited purely for production and/or extraction – but rather as territories for their reproduction as peoples. Although it is necessary to recognize Indigenous land rights and decolonize, we must also recognize that Black people were stolen from their ancestral homes to build settler-colonial wealth and therefore are owed for their labor. Black liberation cannot coexist with the current system of capitalism. At the same time, to live self-determining lives, Black people must control their labor and have access to land to create systems that are affirming and allow them to thrive. Collaborative ownership of land creates a space that heals land-based and racial trauma, contributes to economic sovereignty, and builds movements of justice to reclaim and revitalize cultural practices. This is essential in the fight for Black and Indigenous liberation. Land rematriation and reparations are an essential part of a Just Transition.

Organizations leading the way:

The Sogorea Te Land Trust (USA)

An urban Indigenous women-led community organization that facilitates the return of Chochenyo and Karkin Ohlone lands in the San Francisco Bay Area to Indigenous stewardship. Sogorea Te creates opportunities for all people living in Ohlone territory to work together to re-envision the Bay Area community and what it means to live on Ohlone land. Guided by the belief that land is the foundation that can bring us together, Sogorea Te calls on us all to heal from the legacies of colonialism and genocide, to remember different ways of living, and to do the work that our ancestors and future generations are calling us to do.The Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust (USA)

Works to advance land and food sovereignty through securing permanent land tenure for POC farmers and land stewards who will honor the land through sustainable agriculture, native ecosystem preservation, and preservation of culture.Finger Lakes Land Access Reconciliation & Reparations (USA)

Serves as an information and advisory hub for land reconciliation and reparations in the Finger Lakes region, through the strength and power of collaborating organizations and individuals. We acknowledge the historic meaning and legacy behind the words reconciliation and reparations. We are seeking to create loving and trusting relationships within our communities in the name of sovereignty”A New Land Tenure System (USA)

The Schumacher Center for Economics has been working since its inception on creating non-profit community land trusts to manage natural resources. “A community land trust is a democratically governed, regionally based, open membership non-profit corporation.”Land Trust Alliance (USA)

Founded in 1982, the Land Trust Alliance works to save the places people need and love by strengthening land conservation across the United States.Further Resources:

Translocal Strategies for a Just Recovery: A Black-Led Session on Restoring Land, Labor, and Capital to Self-Determined Communities by Movement Generation

Books, Articles, and Reports:

- Another Future is Possible

- Commons and Enclosure in the Colonization of North America by Allan Greer

- Movement Generation: A Strategic Framework for a Just Transition

Websites & Media:

- Climate Justice Alliance’s Just Transition Framewor

- Reparations Map for Black-Indigenous Farmers

- The Commune: Community Control of the Black Community

Way Forward 3: