Way Forward

Way Forward 1:

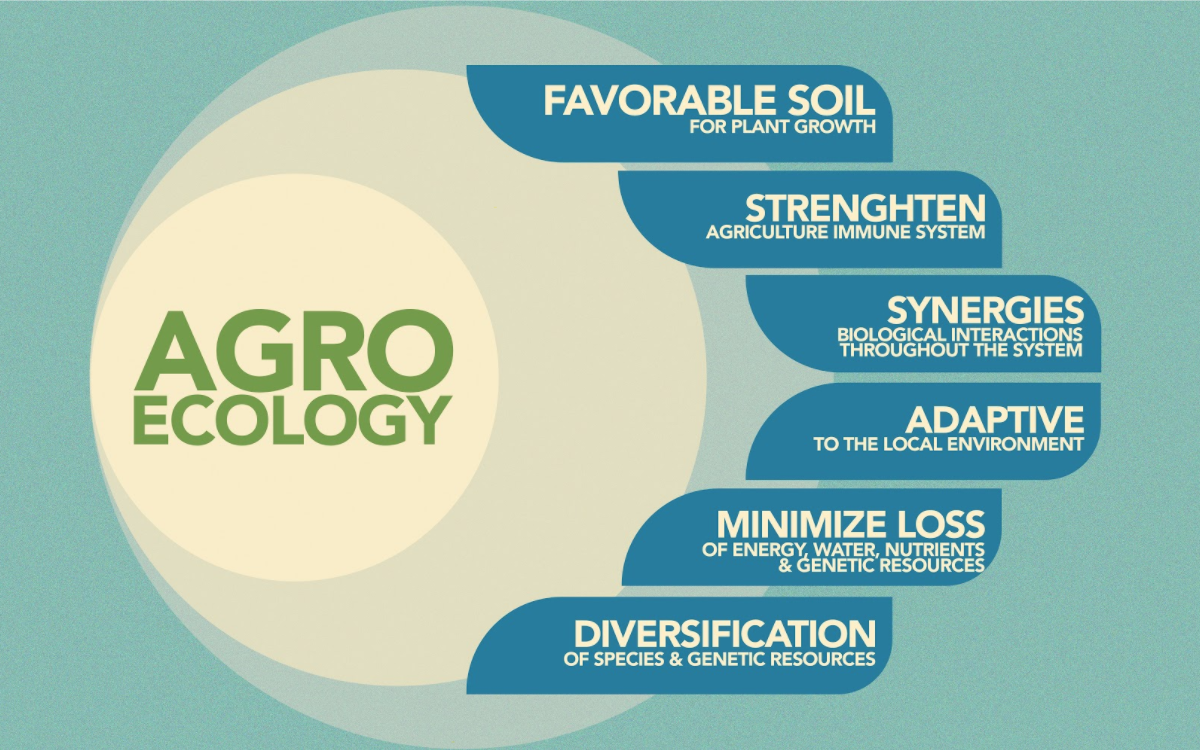

Agroecology:

Agroecology centers the regeneration of the land while providing food, medicine, and other community needs. It is simultaneously focused on biodiversity and cultural diversity, as the two are inextricably linked. There are a vast range of agroecology projects, as each are localized to the needs of their community, human, water, animal, plant, and geological communities included.

Agroecology is the opposite of industrial agriculture. It is a holistic land-based approach to farming practices, knowledge that has been produced and conserved by peasant, Indigenous, and small-scale family farmers around the world.

Source: Altieri, M. A., Nicholls, C. I., Henao, A., & Lana, M. A. (2015). Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agronomy for sustainable development. Design and edit by Christian Tandazo.

Source: Altieri, M. A., Nicholls, C. I., Henao, A., & Lana, M. A. (2015). Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agronomy for sustainable development. Design and edit by Christian Tandazo.

The knowledge of Peasant and Indigenous farmers is the key component in the design of agroecological farming practices. This knowledge is place-based, locally-adapted, and culturally-relevant, which has been passed down through generations. Industrial agriculture poses a threat to this knowledge. Farm land expropriation by agribusiness and transnational corporations continue to displace peasant and Indigenous farmers from their traditional territories, through this process incredible ancestral agricultural knowledge is lost.

(For more on Peasant Right’s please see “Way Forward 5”)

Agroecology small-scale family farming in Catacocha, Loja, Ecuador. Photo Credit: Christian Tandazo

Agroecology small-scale family farming in Catacocha, Loja, Ecuador. Photo Credit: Christian TandazoAs farm management practice, agroecology would: drastically reduce the use of fossil fuels for chemical and synthetic fertilizers, and pesticide production used in conventional agriculture; potential to mitigate through soil and plant rejuvenation for carbon sequestration; stormwater filtration; has the flexibility and diversity required to allow adaptation for changing climate conditions; and ensure food security.

Some of the multiple benefits of Agroecology include:

- Provide stable yields and tackle hunger: agroecological systems chieve more stable levels of total yield per unit area.

- Linking food to territories

- Nutrition, health and sustainable livelihoods

- Preservation and sharing of cultural diversity and knowledge

- Transparency and access to information

- Central role of rural women

- Restoring ecosystems, soil health, and preserving biodiversity

- Preservation and renewal of genetic resources.

- Harnessing food systems to stop climate change

- Resilience to conflict and environmental disasters.

Agroecology requires we partake in a global paradigm change in our social, political, economic, and cultural relations and structures, but most importantly a change in the relationship between nature and society.

As the climate crisis increases the uncertainty of raising temperatures, intense storm patterns, droughts, and recently the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative we transition from industrial agriculture towards agroecology and food sovereignty. Agroecology is the only model capable of feeding millions of people and addressing the climate crisis, however, this can only be achieved under the leadership of its protagonists: Indigenous, peasant, and small-scale family farmers.

Organizations leading the way in Agroecology:

Black Earth Farms Collective (USA)

Black Earch Farms Collective is composed of skilled Pan-African and Pan-Indigenous peoples who study and spread ancestral knowledge and contemporary agroecological practices to train community members to build collectivized, autonomous, and chemical free food systems in urban and peri-urban environments throughout the Occupied Karkin Ohlone & Chochenyo Territory.Asociación ANDES (Peru):

A Quechua organization that promotes the rights of Indigenous peoples and the biodiversity of food and agricultural systems. ANDES works to support Indigenous peoples through independent research and analysis, strategies based on the development of collective biocultural heritage, networking at the local, regional and international levels, and the promotion of new forms of cooperation and alliances.Soul Fire Farm Inc. (USA):

A BIPOC-centered community farm committed to ending racism and injustice in the food system. With deep reverence for the land and wisdom of our ancestors, we work to reclaim our collective right to belong to the earth and to have agency in the food system. Universidad Ixil (Guatemala)

This University challenges western educational models. The university prioritises oral tradition over written and within its curriculum, promotes the ancestral knowledge born of that same land. Students engage in extensive fieldwork and research in their own communities, with the elders and Indigenous authorities as their principal sources of information.Focus on the Global South (Global)

Focus on the Global South is an activist think tank in Asia providing analysis and building alternatives for just social, economic and political change. One of the issues they cover is Food Sovereignty and Agroecology. Organización Boricuá de Agricultura Ecológica de Puerto Rico

Organización Boricuá, a member organization of La Via Campesina is a grassroots organization that was founded 30 years ago and is one of the leaders of the agroecology movement in Puerto Rico working to connect, teach, and support farmers and spread the use of agroecology across the country.Proyecto Agroecológico El Josco Bravo

Josco Bravo is an agro-ecological production and education project located in the foothills of the town of Toa Alta, Puerto Rico.More Resources on Agroecology:

Books, Articles, and Reports:- Asociación ANDES Knowledge Portal

- BIPOC Led Gardening Projects

- Duru, Michel, Olivier Therond, and M’hand Fares. 2015. “Designing Agroecological Transitions; A Review.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35(4): 1237–57

- Farming While Black by Leah Penniman

- Friends of the Earth International. 2018. “Agroecology: Innovating for Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems”. Who Benefits? Series. 1-32.

- Figueroa-Helland, L., Thomas, C., and Pérez Aguilera, A.. (2018). “Decolonizing Food Systems: Food Sovereignty, Indigenous Revitalization, and Agroecology as Counter-Hegemonic Movements.”

- Food & Land Sovereignty Resource List for COVID-19

- Gliessman, Stephen M. (2008). “Agroecology and Agroecosystems.” In Sustainable Agriculture and Food, Agriculture and the Environment, London: Earthscan.

- IPES-Food. (2018). Breaking Away from Industrial Food and Farming Systems Seven: case studies of agroecological transition.

- IPES-Food. (2016). From Uniformity to Diversity: A paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems.

- Ixil University and the Decolonization of Knowledge by Giovanni Batz

- World Forum of Fisher Peoples. 2017. “Agroecology and Food Sovereignty in Small Scale Fisheries”. Transnational Institute.

- Roces, Irene García, Marta Soler Montiel and Assumpta Sabuco i Cantó. 2014 “Perspectiva ecofeminista de la Soberanía Alimentaria: La Red de Agroecología en la Comunidad Moreno Maia en la Amazonía brasileña.”

Way Forward 2:

Indigenous Forest Gardens

Indigenous Forest Gardens, Forest Garden Systems, and Sacred Forests are highly biodiverse and sustainable agroforestry systems which have been cultivated and nurtured by indigenous peoples.

Forest Gardens are based in polyculture, symbiotic plant relationships, cycles of forest and plant growth, a cosmology of the land as sacred, and traditional ecological knowledge and practices that have been passed down through generations.

The Mayan Milpa system is practiced by most rainforest populations close to the equator, the most densely biodiverse areas in the world today and the locations at highest risk for biopiracy and extractivism. Milpa systems run over cycles of time, not singular farming seasons. Traditionally the cycle might be anywhere from 30 to 50 years, with over 1300 species throughout a given cycle.

These systems include agroecological methods such as partial burns to enhance plant growth followed by the introduction of small crops such as maize. Indigenous forest gardens not only have been proven to increase forest biodiversity, but give communities and towns food sovereignty.

Forest garden systems are used around the world; in India, over 100,000 sacred forests exist. Forest gardens and sacred forests have a high number of medicinal plants and higher species diversity than surrounding forests and even government-protected forestland. Nowadays, the Milpa exists in addition to the home garden and a middle distance garden.

Forest gardens are but one example of agroecology and are based in indigenous cosmologies that surround the sacredness of the land. As many of these practices have been decimated over time through settler colonialism, indigenous led initiatives such as the Zapatista Food Forest, are working on ways to recover, teach, and preserve indigenous knowledge and practices.

Organizations leading the way in Indigenous Forest Gardens:

MesoAmerican Research Center:

The MesoAmerican Research Center seeks to develop a broad understanding of the people, cultures, and environment of the greater Mesoamerican region of Mexico and Central America. Research of the center has emerged in the context of Anthropology and Archaeology, yet is wholly interdisciplinary in focus. The MesoAmerican Research Center continues to maintain its focus on the Maya forest and the broad fields of study in the region. El Pilar Forest Garden Network (Guatemala)

The El Pilar Forest Garden Network is a group of Maya farmers who are keeping alive Maya cultural traditions, promoting sustainable agriculture, conserving biodiversity in the Maya Forest, and educating the public on the value of their time-honored strategies.Forest Peoples Programme:

The Forest Peoples Programme is a human rights based organization that works with forest peoples globally to secure their rights to land and livelihoods. FPP works to support indigenous organizations and forest peoples in advocating for indigenous forest management and assists with handling outside powers that threaten indigenous land rights.More Resorces on Indigenous Forest Gardens:

- The Maya Forest Garde: Eight Millennia of Sustainable Cultivation of the Tropical Woodlands. By: Anabel Ford and Ronald Nigh

- Barbhuiya, A., U. Sahoo, and K. Upadhyaya. 2016. “Plant Diversity in the Indigenous Home Gardens in the Eastern Himalayan Region of Mizoram, Northeast India.” Economic Botany 70(2): 115–31.

- Campanha, Mônica Matoso et al. 2004. “Growth and Yield of Coffee Plants in Agroforestry and Monoculture Systems in Minas Gerais, Brazil.” Agroforestry Systems 63(1): 75–82

- Gabay, Mónica, and Mahbubul Alam. 2017 "Community Forestry and Its Mitigation Potential in the Anthropocene: The Importance of Land Tenure Governance and the Threat of Privatization." Forest policy and economics, v. 79, pp. 26-35.

- Wartman, Paul & Acker, Rene & Martin, Ralph. (2018). Temperate Agroforestry: How Forest Garden Systems Combined with People-Based Ethics Can Transform Culture. Sustainability. 10. 2246. 10.3390/su10072246.

- Ormsby, Alison & Bhagwat, Shonil. (2010). Sacred Forests of India: A Strong Tradition Of Community-Based Natural Resource Management. Environmental Conservation. 37. 320 - 326. 10.1017/S0376892910000561

- IWGIA, PINGOS. Tanzania Indigenous People Policy Brief: Climate Change Mitigation Strategies and Eviction of Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral lands: The Case of Tanzania

Way Forward 3:

Queer & Trans Liberation / Gender Justice

“Mainstream understandings of botany and ecology have been used to justify violence against queer, trans, indigenous, and people of color; female, disabled, and marginalized bodies. The field of queer ecology seeks to reimagine the natural world in a way that values and affirms all life.” - Moretta Browne, Clare Riesman, and Edgar Xochitl

Queer and Trans Liberation, along side Gender Justice has been put forth as a solution for climate justice by many BIPOC women, trans people, and two spirit leaders because an analysis of gender and the violences it inflicts through patriarchy, homophobia, and transphobia, directly underpins the roots of the climate crisis. As shown in the sections above, food sciences have been deeply influenced by capitalism. Queer ecology rejects hetero-patriarchal science norms and forms of linear understanding.

It’s clear that women, trans people, and two spirit people are disproportionately left on the front lines and bear the brunt of climate change as a convergence of crises. As such, attention and efforts need to be focused on securing their safety, autonomy, and futures – these must be pursued through gender self-determination, and redistribution of resources, not a top down approach.

Furthermore, many BIPOC women, queer people, trans people, and two spirit people have been, and are already building resilient futures out of necessity. Mutual aid efforts around food security, healthcare access, diaster relief, harm reduction and more, are all efforts born from BIPOC queer communities because the system today has never worked for them. When looking towards solutions to building community resiliency that prioritizes agency of us that are most vulnerable, the BIPOC queer community is leading the way.

Organizations leading the way:

Our Climate Voices

Our Climate Voices seeks to make climate change personal through localized and community based storytelling and organizing. They put together a great listening series on the relationship between Climate Justice and Queer and Trans Liberation. La Via Campesina

La Via Campesina, the largest international member based peasant’s movement, prioritizes the needs of women because they see “Food Sovereignty as a feminist issue.” Practices such as Agroecology and food sovereignty promote women’s autonomy as when capitalism and the norms of domination of women by men and men of the earth are abolished, all life becomes safer.- Keeping the Struggles of Peasant Women Alive, La Via Campesina

- Women’s struggles for a Peasant and Peoples’ Feminism

More Resources on Queer & Trans Liberation / Gender Justice:

- Brady, A., Torres, A., & Brown, P. (2019). What the queer community brings to the fight for climate justice.

- Brimm, Katie. (2019) We are Natural: California Farmers Reimagine the World through Queer Ecology

- Kabir, Kareeda. (2018) How Climate Change in Bangladesh Impacts Women and Girls, NYU Press. Queer Ecology

Way Forward 4:

Peasant Rights

Peasants, small scale farmers and fishers, family farmers, pastoralists, hunters and gatherers, have been at the forefront of the fight for food sovereignty against agribusiness and transnational corporations. Unfortunately, taking a stand against corporations has propelled violence agaisnt peasants and workers, as more people continue to be displaced from their traditional farming lands at the hands of agribusinesses and transnational corporations. They have been criminalized or even killed for the simple act of saving seeds to feed their families.

Peasants are safeguards of agrobiodiversity, biocultural diversity, and traditional agricultural knowledge that foster a relationship of reciprocity, with the land, water, soils, non-human kin, and microbial diversity. Peasants also care for seeds, contributing to global seed diversity by protecting and sometimes interbreeding 50,00 - 60,000 wild relatives of cultivated species at no cost.

Through these practices, peasants have become the main or sole food providers to more than 70% of the world’s population, while Industrial Agriculture only feeds 30%. Peasants produce this amount of food with less than 25% of the resources the industrial food system uses - including land, waste, fossil fuels - used to get all of the world’s food to the consumer’s table.

The ancestral knowledge and practices that peasants hold are vital to global food security, provide an opportunity to drastically reduce emissions from the agriculture sector, revitalize depleted soils, preserve biodiversity, and produce healthy and culturally relevant foods.

However, peasants alone won’t be able to solve the world’s crises and threats to food security, therefore, it is imperative to show support for peasants in the fight and struggle for their rights, whether at the policy level or on the ground.

Organizations leading the fight for Peasant’s Rights:

La Via Campesina (LVC)

LVC is the largest transnational agrarian movement today. LVC actively builds alliances with other social movements, bringing together millions of peasants, small and medium size farmers, landless people, rural women and youth, indigenous people, migrants and agricultural workers from around the world; trying to respond to the impacts of capitalist development in food, agriculture and land-use. LVC is mainly recognized for championing and developing the Food Sovereignty paradigmLVC is built on a strong sense of unity, solidarity, it defends peasant, Indigneous and small-scale family farmers for food sovereignty as a way to promote social justice and dignity and strongly opposes corporate driven agriculture that destroys social relations and nature.

- Illustration - UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP)

- The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants: A Tool in the Struggle for our Common Future

Movimiento Campesino a Campesino (MCAC) - (Central America and Cuba)

MCAC, or Farmer to Farmer, is a grassroots movement that originated in the early 1970s in Guatemala and expanded to Mexico, Nicaragua, and Cuba. It was pioneered by Mayan campesinos who applied methods of soil and water conservation in their farming practices. They later proceeded to share this knowledge with other peasant farmers in Mexico. This was has been described as peasant pedagogy, which generates effective site-specific agroecological solutions, encourages forms of non-hierarchical communication and leadership structures. This for of pedagogy was later spread throughout Central America and the Caribbean.The peasant seeds network (France)

The Peasant Seeds Network leads a movement of collectives rooted in the territories which renew, disseminate and defend peasant seeds, as well as the associated know-how and knowledge.These collectives are inventing new seed systems, a source of cultivated biodiversity and autonomy, in the face of the industry's monopoly on seeds and its patented GMOs.

More Resources on Peasant Right’s:

- Bocci, R. & Chable, V. (2009). Peasant seeds in Europe: stakes and prospects.

- ETC Group. (2017). Who Will Feed Us?: The Peasant Food Web vs. The Industrial Food Chain.

- Gevers, C., van Rijswick, H., & Swart, J. (2019) Peasant Seeds in France: Fostering A More Resilient Agriculture

- Rosset, Peter & Sosa, Braulio & Jaime, Adilén & Avila, Rocio. (2011). The Campesino-to-Campesino Agroecology Movement of ANAP in Cuba: Social Process Methodology in the Construction of Sustainable Peasant Agriculture and Food Sovereignty.