Who’s In The Way

Who’s In The Way

Obstacle 1:

Global Military Apparatuses

(NATO, the US Pentagon & Others)

After the Cold War and the diminishment of traditional military threats, security institutions such as the US military and NATO began to broaden the scope of issues they examined, issues classified as “low politics.” The environment became a global security issue.

Military apparatuses, such as the Department of Defense, project resource scarcity and climate security language to fuel more armed conflict and serve the interests of the status quo.

Commissioned by the former Royal Dutch Shell planner Peter Schwartz, the 2003 Pentagon Report “An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for United States National Security” depicted dystopian and apocalyptic scenarios of climate change. This contributed even more to alarmist media narratives.

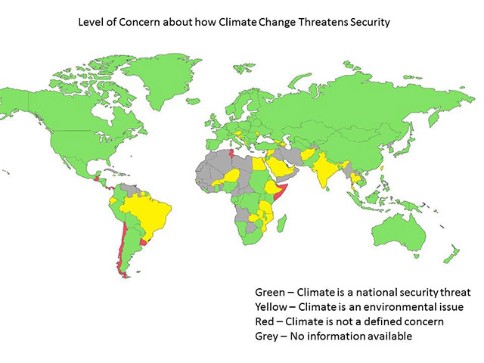

In 2008, the EU followed suit by publishing a report on climate change and international security, defining climate change as a ‘threat multiplier’ affecting EU own security and interests. Fast forward to 2021, President Biden declared climate change a national security priority, NATO created an action plan on climate and security, the UK declared it was moving to a system of “climate-prepared defense,” the EU developed a Climate Change and Defense Roadmap, and the UNSC held a debate on climate and security.

As the biggest global polluters, the growing spending budget of the military industry contradicts its so-called commitments to ‘greening’ their militaries. Recent data by SIPRI shows that global military spending has surpassed $2 trillion in 2021 for the first time.

The Pentagon alone is the world’s largest consumer of fossil fuel. Because military emissions reporting is only voluntary, there is a lack of transparent data and therefore the absence of accountability mechanisms. A 2019 study by Brown University estimated that more than 440 Million Metric tons of CO2. have been consumed by the U.S. military alone since the beginning of the War on Terror in 2001 (all war-related emissions including the major war zones of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and Syria). According to the same study, the amount of emissions by the US military is larger than the emissions of many countries, as well as greater than all CO2 emissions from US production of iron and steel.

U.S imperialism has a long toxic environmental legacy. Some examples include chemical contamination left in Afghanistan, the nuclear contamination in the Marshalls Islands and the colonial contamination in Guam.

A military nuclear waste dome, named by locals ‘The Tomb’, containing more than 3.1 million cubic feet of radioactive waste on the Enewetak Atoll of the Marshall Islands.

(Source: The Asahi Shimbun / Getty Images)

(Source: The Asahi Shimbun / Getty Images)

Besides Western military apparatuses, there is an emerging trend of countries of the Global South with large military apparatuses and/or authoritarian regimes that are also adopting a climate security approach. There is no blueprint for how each country in the Global South is engaging with climate besides sharing colonial histories from US and European imperialism. However, while the Group 77 serves as a proxy for the Global South, in the past 15 years positions on climate and security have been changing. For example, small island and developing countries, especially in the Pacific, have also been adopting a security framework.

Examples include Brazil, India, Pakistan, Egypt, Philippines and the Sahel region. India for example is the third largest military spender and while it claims to oppose the UN Security Council’s climate security approach, the Indian military’s responses to climate change reflect that its military has in fact embraced the national and international climate security discourse to legitimize its role as the country’s central security agent. The 2017 Joint Doctrine of the Indian Armed Forces adopts the ‘threat-multiplier’ rhetoric and lists climate change, environmental disasters, and resource security among others as “non-traditional external threats” to Indian national security, possibly requiring the military to respond to such threats.

A 2022 report on the Bay Of Bengal, one of the most climate-vulnerable regions in the world, adopts the language of climate as a threat-multiplier, focusing on the climate impacts on military assets and operations, and viewing climate-induced migration as a major conflict driver

We can see a parallel with the ongoing Russian invasion in Ukraine: sending US weapons to Ukraine and more troops through NATO and imposing draconian sanctions on Russia will only escalate the crisis and cause devastating environmental consequences. See NDN Collective’s article that lays out implications this attack has for human rights and the climate crisis.

Campaigns against NATO: No to Nato Campaign

Obstacle 2:

Transnational Corporations

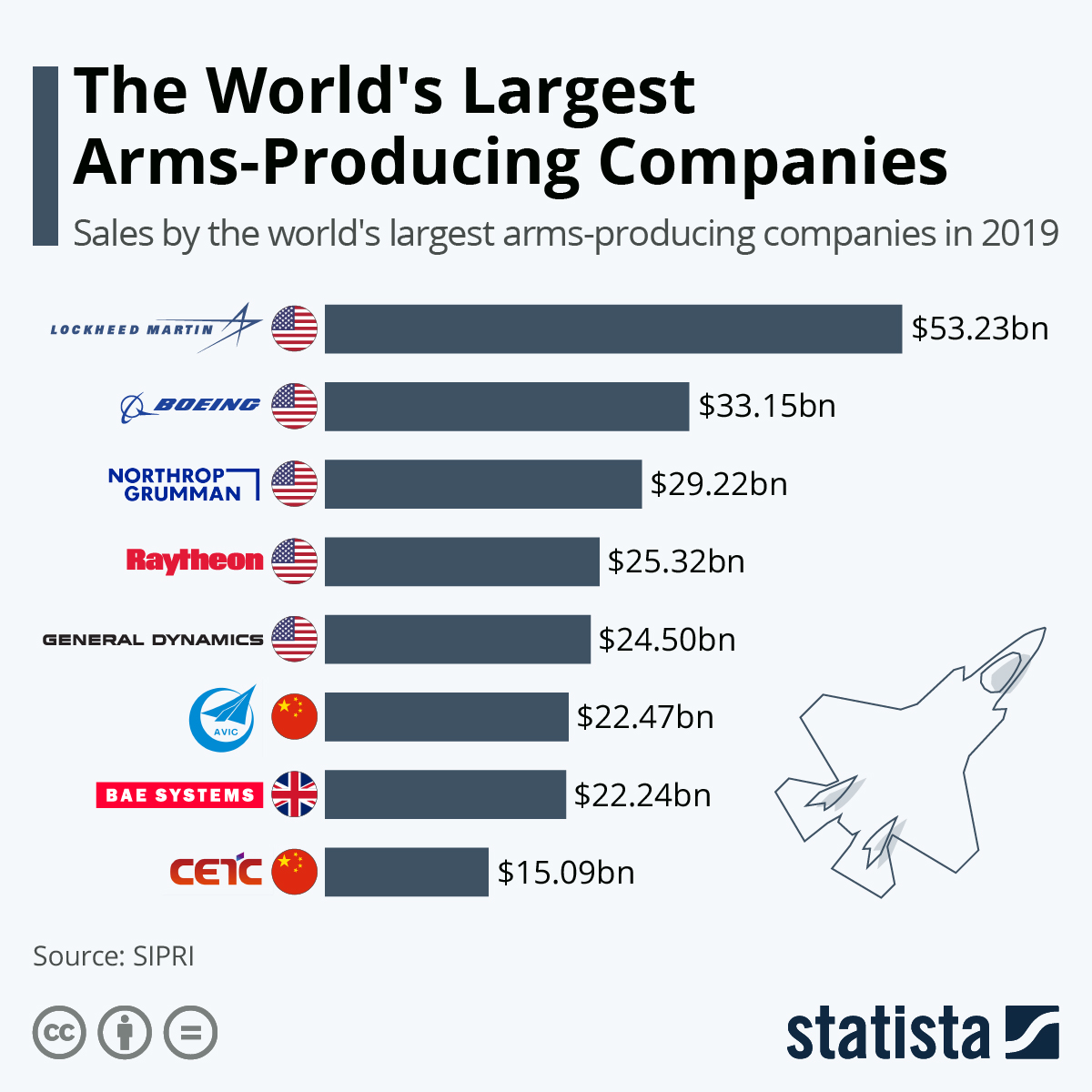

The lines between industries and governments are increasingly blurred as transnational corporations directly influence much of the decision making around national security. Transnational corporations (TNCs), especially those in the arms, aerospace, security, and fossil fuel industries both advocate for and reap the largest profits from the climate security approach and its heightened militarization, globally. The largest five arms and military service corporations reaping these profits are Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, and General Dynamics, all of which are headquartered in the US, followed by companies based in China and Europe.

Source: Statista

These war profiteers are involved in powerful and consistent lobbying to ensure rising military budgets. Substantial portions of these budgets are allocated to awarding contracts to arms, aerospace, border security, cyber security (surveillance), and homeland security firms.

From 2001 to 2021, the arms industry made campaign contributions totalling $285 million spanning US parties and offices who have influence over military budgets in addition to $2.5 billion on lobbying, all of which have been quite successful in promoting their interests.

People from these industries and governments increasingly pass through the revolving door going from positions in one sector to the other, and influencing policy in favor of defense industries. The past four of five US Secretaries of Defense were previously executives at some of the top weapons contractors (General Dynamics, Boeing, Raytheon).

Defense contractors also fund many well-known think tanks that champion increasing military budgets. The top 50 think tanks in the U.S. received $1 billion in funding from weapons firms between 2014 to 2019 (largest contributions from Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, Boeing, Lockheed Martin and Airbus). There is a growing list of non-military and civil society think tanks advocating for greater attention to climate security:

- CNA

- Brookings Institute (US)

- Council on Foreign Relations (US),

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (UK)

- Chatham House (UK),

- Center for Climate and Security

- International Military Council on Climate and Security

- Center for New American Security

- Center for Strategic & International Studies

Contracts are awarded both in anticipation of climate change and migration related ‘instability,’ as well as towards ‘green’ technologies that are less reliant on fossil fuels and more resilient to climate change impacts. The Pentagon awarded a contract worth $89 million to Boeing in 2010 to develop a ‘SolarEagle’ drone. In 2013, the Pentagon also spent $5 million on the development of lead-free bullets.

The top five defense corporations, Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, and General Dynamics, won one-quarter to one-third of all Pentagon contracts in recent years, totalling $2.1 trillion between 2001 to 2021. Approximately 85% of Boeing’s annual revenue comes from contracts with the U.S. government and sales to foreign militaries. Additionally, Boeing received over $21 billion in 2020 and $60 million in tax breaks from the City of Chicago where Boeing is headquartered.

TNCs in these industries recognize the market opportunities present in climate security and related environmental initiatives and are making sure to invest in and promote such initiatives. The Energy Environmental Defense and Security Conference in Washington, DC in 2011, claimed that environmental markets presented a business opportunity eight times that of the current defense market for the defense industry.

Despite the promotion of ‘green’ renewable technologies, militaries still depend largely on fossil fuels to operate high-energy technologies and transportation. This results in contracts for fossil fuel companies to sustain war-making, as well as war-making to ensure continued access to fossil fuels and transhipment routes globally.

More Resources on War Profiteers:

Books, Articles, and Reports:- Who Profits from War

- Industry cash, not public opinion, predicts Democrat votes on defense - SPRI

- Weapons Industry Exploits Ukraine War as Profits Pile Up by Sarah Lazare

- Energy, Capital as Power, and World Order by Tim Di Muzio

- Divest From Death Campaign - We are Dissenters

Media:

Obstacle 3:

Global Governance Structures

In the post-Cold War system, the main project of the governance mechanisms is the legitimization and the extension of the ruling institutions of the global status quo. These institutions include NATO, the IMF, the World Bank, the UN, the US, and the G8/G20. This system utilizes and devises methods, – particularly the use of organized violence – to help maintain an unequal international order, premised on the primacy of capital, racial and gendered violence, as well as US geopolitical power. The promotion of a Western neoliberal development model is, in the words of Stephen Gill, “baked in through the systematic use of military power and related geopolitical practices,” such as those of diplomacy, intelligence, surveillance and covert mechanisms of intervention. The proper, strategic response to global environmental crises involves the expansion of state-military capabilities in order to strengthen the centralized governance structures whose task it is to regulate the international distribution of natural resources, as well as ensure that a particular state’s own resource requirements are protected. Gains from one state are losses for another. Below, three different governance mechanisms used to securitize climate change are explored more in depth.

The UN:

The climate is increasingly and systematically referred to as a “threat multiplier” within the UN system. This consistency appears in the 2009 UN General Assembly resolution A/63/281, titled “climate change and its possible security implications.” This resolution cautioned its members to “consider the possible security implications of climate change impacts.” This framing also appears in various reports and debates held by numerous UN bodies including UN Environmental Program, UN Climate Security Mechanism, Group of Friends, and UN Secretary General Address to Security Council. The UN, the UK and other Western nations, have been amongst the chief proponents of crafting and endorsing the concept of climate security on an international level by noting that climate is not just an environmental problem, but rather threatens the status quo referenced above. More recently, as world leaders met in Glasgow for the COP26 climate summit, activists and scholars gathered in an Arctic basecamp tent in the city for a panel discussion on the state of military emissions and to launch a new website dedicated to corralling disparate emissions reporting. Crucially, this site pulls government reporting on countries’ military emissions, in addition to other relevant data like gross domestic product and military expenditure, into one database which allows for easier comparisons to be made between countries. Military emissions are substantial contributors towards the destabilization of the climate and yet, military emissions continue to be absent in the formal agendas at UN meetings. This has not gone unnoticed as more than 200 civil society organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, signed on to the Conflict and Environment Observatory’s call for governments to commit to meaningful emissions reductions ahead of the summit. During protests at COP26, climate activists called out the U.S. military specifically for its role in climate change. The UN’s framing of the conflict, via the language of security and the normalization of securitizing ‘solutions’ inevitably shows that there is a crisis within the global governance institutions as they are unable to offer pathways forward away from patriarchal, neoliberal logics of domination.

The UNSC:

Source: International Crisis Group

Source: International Crisis GroupThe securitization of climate change within the UN Security Council has often highlighted the manner in which climate change and extreme weather events can exacerbate societal and cross-border stressors,with potential consequent political and security impacts. A further UN Security Council debate was held just two years later in 2011, with renewed focus on links between human mobility, environmental refugees, and disaster-related displacement. Once again, multiple actors cautioned against the encroachment by the Security Council on matters on climate, with nations drawing concern over the securitization of climate in lieu of addressing the political, economic, and humanitarian aspects. Viewing climate change through a securitizing lens enables the UNSC, comprised of countries who are historically most responsible for the destabilization of the climate , to deflect attention from their own culpability. The Security Council, through the continued securitization of climate change, and continued pushing of this agenda upon the Global South, further perpetuates ecocide, genocide, power inequalities, and masculinist notions of what solutions are available.